What could actually make Bay Area crime go down? Studies have fascinating theories

[ad_1]

Ask residents in the San Francisco Bay Area what their most pressing regional concern is right now, and a large percentage of them will likely say crime. High-profile robberies, endless car and garage break-ins and the general sense of unease that comes with it all has crime top of mind for many locals.

And an escalating region-wide conversation around crime has led to a lot of conflicting opinions on what can be done about it.

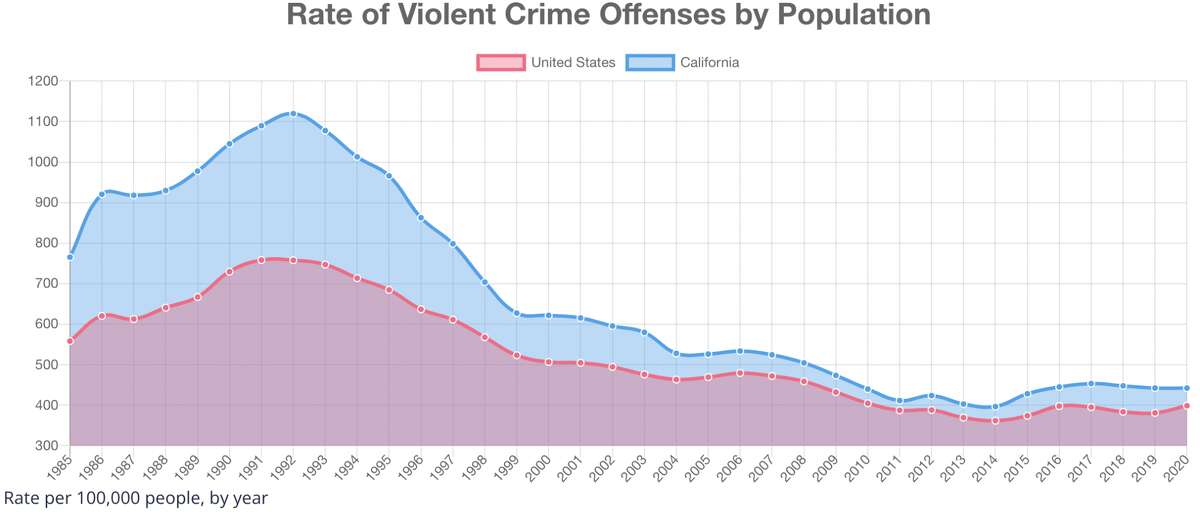

Modern criminologists, scholars and law enforcement agencies have been analyzing crime trends and prevention techniques for decades. Much of the research centers on the 1990s, when the United States experienced a drastic drop in crime. That drop has held steady, and America has yet to see anything like the catastrophic crime rates of the 1970s and 1980s; according to FBI data, the violent crime rate fell a further 49% between 1993 and 2019.

The FBI charts violent crime rates nationwide; rates have been rising in California since a low in 2014.

FBI data“These declines occurred essentially without warning,” “Freakanomics” co-author and economist Steven D. Levitt wrote in his 2004 study “Understanding Why Crime Fell in the 1990s.” “Leading experts were predicting explosions in crime in the early and mid-1990s, precisely the point when crime rates began to plunge.”

Because of the disparity between the chaotic 1980s and declining rates of the 1990s, the two decades are particularly instructive for people looking to see what actually impacted public safety. There’s little everyone agrees on — although some data points correlate, it’s very difficult to assign causality to something as broad and complex as “crime” — but the theories are fascinating. Here’s what a number of prominent researchers have found does and doesn’t seem to alter crime rates.

What doesn’t work?

Buoyed by Malcolm Gladwell’s “The Tipping Point,” the broken windows theory is one of the most famous modern policing axioms. The theory goes that minor quality-of-life issues, like vandalism, jaywalking and loitering, create an unsafe environment where all crime is more prevalent. Former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s “zero tolerance” approach famously focused on policing these types of misdemeanors, and he credited it with NYC’s historic turnaround in the 1990s. “Obviously murder and graffiti are two vastly different crimes,” he told the press in 1998. “But they are part of the same continuum, and a climate that tolerates one is more likely to tolerate the other.”

But despite its fame, there’s little evidence the broken windows theory actually works. For one, Giuliani took office in 1994; Levitt points out that crime in New York City (and nationwide) had already begun its decline several years prior. A 2003 National Bureau of Economic Research study found that while misdemeanor arrests went up 70% in New York City in the 1990s, very few of those offenders ended up with jail time. “Furthermore, an increase in misdemeanor arrests has no impact on the number of murder, assault and burglary cases,” the study asserts.

Levitt agreed. Although NYC was the nation’s most well-known example of being “tough on crime,” Levitt said similar drops were seen in cities that weren’t employing the same tactics. “The universality of these gains [in public safety] argues against idiosyncratic local factors as the primary source of reduction,” he wrote.

A 1997 National Institute of Justice brief came to similar conclusions. The research arm of the US Department of Justice — hardly a bastion of liberal law enforcement policy — reviewed over 500 scientific evaluations of crime prevention methods around the country. Among the methods it listed under “what didn’t work” were: “neighborhood watch programs organized with police,” gun buybacks, adding jail time to misdemeanors that would normally result in just probation, “increased arrests or raids on drug market locations” and arresting juveniles for “minor offenses.”

The brief was particularly critical of arresting young people for small crimes. Studies showed arresting minors increased the likelihood they would be “more delinquent in the future than if police exercise discretion to merely warn them.”

Police being courteous toward suspects correlated with improved outcomes across age groups, the National Institute of Justice analysis found. “Policing with greater respect to offenders reduced repeat offending in one analysis … and increased respect for the law and police in another,” it cited.

What does work?

So what do academics and law enforcement researchers believe actually impacts crime rates? The majority of studies agree that when cities add more police officers, crime tends to go down. The National Bureau of Economic Research study notes that NYC increased its police force 35% in the 1990s, which Levitt cites as a more important factor in lowering crime than heavy-handed policies around petty misdemeanors. The National Institute of Justice found in its studies that adding more patrols to “hot spots” also helped.

Many argue that increased incarceration was an additional factor, but even the DOJ report cautioned that it had limits. “Incarceration of offenders who will continue to commit crime prevents crimes they would commit on the street,” the National Institute of Justice wrote, “but the number of crimes prevented by locking up each additional offender declines with diminishing returns as less active or serious offenders are incarcerated.”

A brief by the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU’s School of Law found California’s prison population rose 514% from 1980 to 2006. The study argues that while mass incarceration did have a temporary effect on the California crime rate, that impact began leveling off by 1997. “The marginal effect on crime of adding more people to prisons remains at essentially zero today,” the brief says.

The robust economy of the 1990s may have also played a role. The minimum wage went up and unemployment went down. Considering we’re currently living through another time of great upheaval due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it stands to reason that economic uncertainty could have repercussions for the current robbery and theft rates, too. (For what it’s worth, Levitt is skeptical that economic indicators are linked; he cites the 1960s as an example of a decade with a booming economy and high crime and social unrest.)

Professors of criminology Mateus Renno Santos and Alexander Testa argued in 2019 that global trends, not local police departments, have the biggest impact on crime. Studies have shown that crime is declining around the world, which suggests “criminal justice policies of individual countries may have less impact on the decline in homicide than world events or trends.” The explanation? An aging population, Santos and Testa say.

“In the United States, rising homicide rates during the 1960s and 1970s paralleled a spike in the young population following the baby boom,” they posit. “For the safest countries, a one percentage point increase in the percent of people aged 15 to 29 corresponds to an increase of 4.6% in the homicide rate,” it adds.

Santos and Testa concluded that “age was the only factor we looked at that consistently predicted homicide increases and declines over an extended period of time.”

And if you want a wild card theory, Levitt points to abortion rates. Levitt cites a study that found women who were denied abortions overwhelmingly kept, not adopted, their baby, leading to resentment of their “unwanted children.” Those children, regardless of the mother’s income and education, grew into adolescents who were more likely to find themselves in legal trouble.

Levitt says that in the decades after Roe v. Wade legalized abortion, those “unwanted children” weren’t born at all, didn’t grow up into teens predisposed to criminal activity, and the nation saw crime dips as a result.

“The five states that allowed abortion in 1970 (three years before Roe v. Wade) experienced declines in crime rates earlier than the rest of the nation,” Levitt writes. “States with high and low abortion rates in the 1970s experienced similar crime trends for decades until the first cohorts exposed to legalized abortion reached the high-crime ages around 1990. …The magnitude of the differences in the crime decline between high- and low-abortion states was over 25 percent for homicide, violent crime and property crime.”

[ad_2]

Source link