Why High-Profile Attacks on SF’s Asian Communities Rarely Lead to Hate-Crime Charges

[ad_1]

Brooke Jenkins, a former assistant district attorney who is now a spokesperson of the recall effort against Boudin, is also a former hate crimes prosecutor in the DA’s office. She said hate crime charges could have been pursued in Zhou’s case using the hateful slur captured on video.

“In my view, in that case, it did meet the bar,” Jenkins said. “There were statements that made the intentions very clear, and [made] the motivations very clear.”

Grayson and Zhou ultimately did not participate in a restorative justice process together, as they initially intended. That process would’ve seen the two men reconcile their differences, sitting together and talking out what happened. In their description of the goal of the San Francisco Restorative Justice Collaborative, the DA’s office specifically points to the method as a practice to encourage multiracial consensus, and global racial solidarity, particularly aiming to repair the relationship between Asian American and African American communities in San Francisco.

In short, it was a process designed to address moments of hate just like this one.

Instead, authorities steered Grayson into another restorative justice path: neighborhood courts. It’s known as a “diversion” program that focuses on rehabilitation and urges participants to take accountability.

Zhou and Grayson couldn’t be reached for comment for this story.

Amerson, who was charged with second-degree robbery and inflicting injury on an elder, was released of his own recognizance with a GPS-tracked ankle monitor. His case is still ongoing.

Notably, Amerson lacked a permanent home when he was arrested for attacking Zhou. He was “mostly transient,” his attorney wrote in a 2020 declaration to the court. Only after his arrest was he able to secure housing, his lawyer wrote, and has been “doing well.”

Boudin touts hate crime charges, even when he’s dropped them

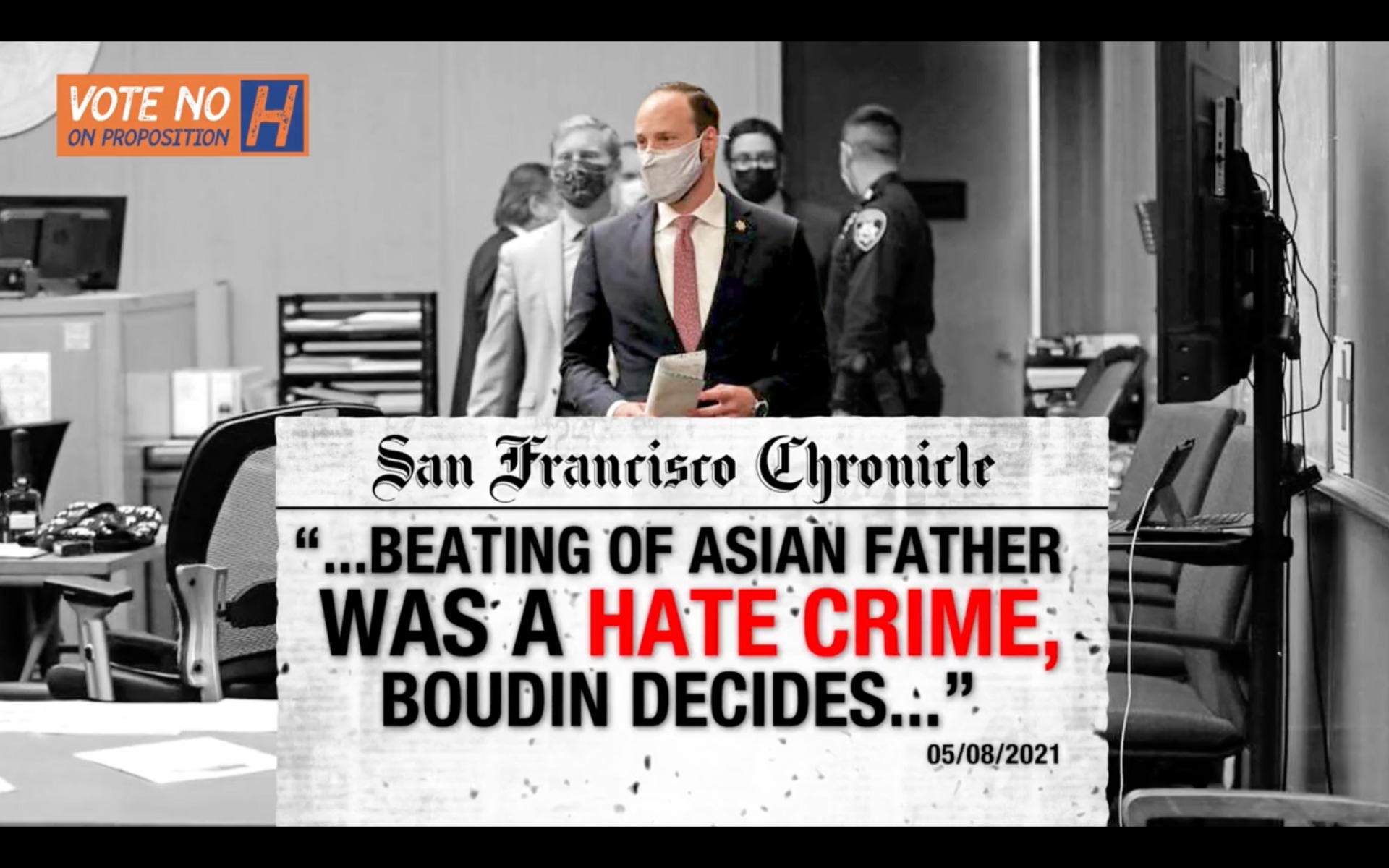

The question of when to charge hate crimes has become a source of contention in the recall election against Boudin. In his own defense, Boudin’s pinned Tweet highlights a video quoting the San Francisco Chronicle, “ … beating of Asian father was a hate crime, Boudin decides.”

But a review of court records by The Standard and KQED shows the hate crime he charged against suspect Sidney Hammond, who allegedly assaulted an Asian father with a baby stroller on April 30, 2021, were eventually dropped.

The DA’s office verified as much, and explained that, after charging, they received additional evidence that did not support hate crime charges, including a San Francisco police officer stating in a report that the incidents were not hate motivated. As such, the office was “ethically obligated” to dismiss the hate crime enhancement.

And no hate-related charges were pursued against the suspect who kicked Liao out of his walker in Tenderloin. According to the latest court documents, Ramos-Hernandez has been referred to mental health treatment and was released with a GPS tracking monitor.

The suspect pushing Ratanapakdee to death, Antoine Watson, remained in custody and is charged with murder. No hate crime-related charges were filed.

Jenkins, who is one of Boudin’s toughest critics, pointed out the importance of charging hate crimes but also acknowledged that hate crimes are notoriously difficult to charge because they hinge on proving intent.

“When you feel like you’re being targeted for that reason, they want to feel vindicated,” said Jenkins. She added that victims of the crime want to see charges that truly capture and reflect the “full scope of someone’s conduct.”

But hate crimes are “one of the only charges that require the DA’s Office to prove motive for the underlying crime,” she said. In other words, it requires that someone has made a verbal expression regarding the victim’s identity, or shows a clear pattern of targeting over time.

There are two cases charged with hate crimes, among the dozen reviewed by KQED and The Standard, and both of them reflect those patterns.

A serial vandalism suspect, Derik Barreto, was charged by DA Boudin for nearly 30 counts of hate crimes as he allegedly targeted Asian-owned businesses, breaking their windows. Barreto provided a lengthy interview with the police explicitly saying he had some delusions “around the surveillance capabilities of Chinese,” court documents reveal. In this case, Barreto verbally admitted targeting Chinese-owned businesses.

But the judge in the case ordered Barreto to be released, even though the DA’s office opposed the decision. After missing his court date, he’s now facing bench warrant arrest.

The other case where hate crime charges emerged involved a suspect robbing multiple Asian women. The suspect, O’Sean Garcia, allegedly showed a pattern of targeting victims with the same racial identity. Garcia was released, too, court records show.

Data from the DA’s office showed that a total of 20 cases included hate crime charges in 2021, both standalone misdemeanors and hate crime enhancements, which are tacked onto felonies.

It’s unclear how many of those 20 cases in 2021 are categorized as anti-Asian as opposed to hate directed toward other identities.

Of course, not every hateful incident is a crime, as the California Attorney General’s Office laid out in a memo explaining the difference between the two.

“The U.S. Constitution allows hate speech as long as it does not interfere with the civil rights of others,” the office wrote in the advisory. “While these acts are certainly hurtful, they do not rise to the level of criminal violations and thus may not be prosecuted.”

Solving hate through community — and data

In mid-May, leaders from San Francisco’s Chinese and Black communities came together at a press conference at Third Baptist Church in the Western Addition to urge authorities to pursue more hate crime charges.

“Public safety is every human being’s birthright,” SFPD Capt. Yulanda Williams said. “Exploitation of our Asian-Pacific Islander community will no longer be tolerated.”

That joint press conference between Black and Asian leaders at Third Baptist Church was convened with the idea that the Black community needed to stand in solidarity with Asian people in calling for more hate crime enhancements, upping the charges suspects face. But Tinisch Hollins, head of Californians for Safety and Justice, said sometimes people react to crime with efforts that ultimately perpetuate racism, and racial injustice.

“There’s a very real sentiment that there are populations of individuals who cause problems and make the city and community unsafe and less desirable,” Hollins said. “And Black people, specifically Black men and boys, are at the top of that list.”

Indeed, the high-profile cases reviewed by KQED and the SF Standard feature a mix of suspects, across various ethnicities.

While public discussion around Asian communities frequently references the need for more safety — pushing that word, “safety,” in particular — Hollins said that can be a societally palatable code for pushing out Black people.

“‘Public safety’ right now, I feel like it’s a very covert way of naming it,’” she said. It also focuses solutions on incarceration instead of giving mental health help, housing, and education to people who may need it in order to reduce incentives for crime.

And, importantly, research shows steeper charges — which hate crime enhancements would bring — and longer sentencing don’t reduce crime.

Magnus Lofstrom, a senior fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California, said his research on Proposition 47, which reduced some felony thefts and drug offenses to misdemeanors, has shown that reducing prison populations doesn’t lead to a rise in violent crime.

Hollins was raised in the Bayview where Zhou was attacked, and said she wasn’t surprised that initial attempts to make peace between Zhou and Grayson bore no fruit. Immigrants, she finds, tend to be suspicious of those kinds of restorative justice approaches, which need community backing to really work.

“If we at all agreed that there are better ways to resolve the kind of social conflicts that come up in our communities, especially when racial tensions are involved,” she said, “you might have a lot more buy-in.”

Both hate crimes and hate incidents are significantly underreported, Lofstrum added. Asian American and Pacific Islander immigrant communities face particular barriers to reporting due to insufficient language access.

Underreporting is a phenomenon state officials are trying to fix.

[ad_2]

Source link