Do armed teachers improve school safety?

[ad_1]

Do armed teachers improve school safety? That question has been hotly debated in recent years following the tragic shootings we have seen at schools across the country including the May 24 shooting at the Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas.

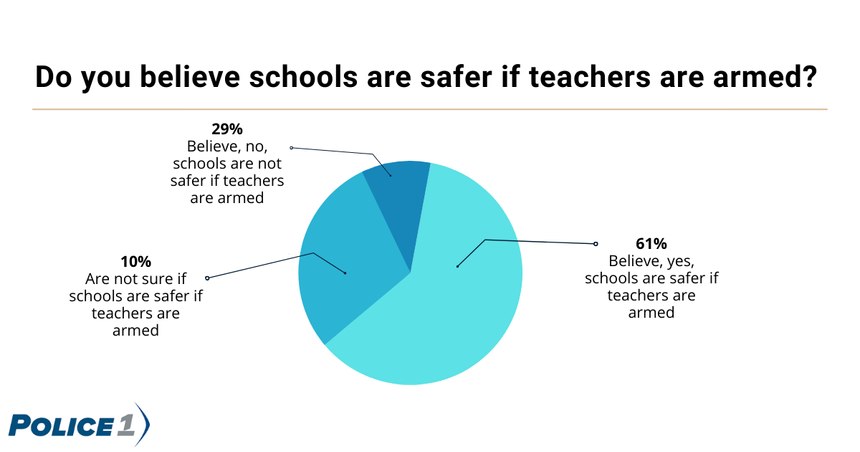

We asked Police1 readers if they believe schools are safer if teachers are armed. Nearly 1,000 respondents answered our poll. Sixty-one percent of you do think schools are safer if teachers are armed, while 29% do not.

Read our columnists’ take on this issue and share your opinion below.

The ground rules: As in an actual debate, the pro and con sides are assigned randomly as an exercise in critical thinking and analyzing problems from different perspectives.

Our debaters: Jim Dudley, a 32-year veteran of the San Francisco Police Department where he retired as deputy chief of the Patrol Bureau, and Chief Joel Shults, EdD, who retired as chief of police in Colorado.

Joel Shults: As a local school board member, the Uvalde school shooting has re-ignited interest in strategies to deal with intruder violence. One of my frustrations is that, even though I am a concealed carry holder who religiously exercises the carrying part (I don’t do LEOSA), Colorado law makes me a felon if I walk onto school property with any of my small arsenal. This effectively creates one of those fictional gun-free zones we hear so much about.

The core problem of immediate response to an immediate deadly threat on the sanctity of school grounds is waiting for the police to arrive. While the idea that we can predict what a violent attack will look like is unrealistic, one of the few constants in such events is the reality that time spent waiting for law enforcement response is free time for killing to the attacker. Even when a police officer is present or nearby, the ability to have a god-like omnipresence on every acre and square foot of school property simply doesn’t exist.

What if an attacker didn’t know whether they would confront armed resistance before they heard sirens or police commands? What if a counterattack came from inside the classrooms and hallways instead of from outside the doors of the school building? It seems to me that the deterrent value of armed school staff would weigh in heavily in favor of gun-toting schoolteachers.

In an examination of 433 school shootings published in “The New York Times,” 249 ended before any law enforcement arrived. Of the remaining 184, police shot the attacker in 98 cases, otherwise subduing them in 33 cases. Comparatively, bystanders interceded prior to police arrival in 64 cases, 22 by shooting and in 42 by subduing them by other means. (In 10 of the 22 shootings the person using a firearm to end the attack was either a security guard or an off-duty police officer). What I see in these stats is an argument for pre-police intervention, and there would surely be some school staff willing and able to pack a pocket pistol with their brown bag lunch.

Jim Dudley: I am not sure how to say exactly how wrong this idea is without insulting the teaching profession, but I’ll try. There are so many variables when it comes to arming someone with a firearm with an expectation that they may have to use it on another person.

I have a perspective of both sides of this argument, after serving over 30 years in a large metropolitan city. I have been in armed encounters where the offenders were armed with blunt and bladed instruments and on a few occasions, they were armed with firearms. I used my firearm against another person in one encounter, and if I hadn’t, someone else would be writing this side of the argument.

I also have the perspective as a teacher, serving for the past 10 years as a full-time member of the criminal justice studies faculty at my university in San Francisco.

No teacher ever signed up to train with and to carry a firearm. There are certainly some teachers who should absolutely not be armed with a firearm in a school setting. The expectations of both professions overlap with some similarities, but they are more disparate than similar.

Police officers go through vigorous testing from the beginning, with written, oral and physical testing that they must pass above the standard, only to go on to further batteries of psychological testing, a polygraph test and intensive background research. One segment of the 30 weeks or so of academy training involves learning about the nomenclature of the firearm, the circumstances of when to draw it and when to use lethal force upon another. Case laws are reviewed, simulations are experienced, and officers must learn the nuances of force options, resorting to the firearm, only as a last resort. Another 16 to 24 hours (or more) is dedicated to learning about positioning and shooting at targets from 3,5,7,15 and 25 yards or more at a silhouette in the shape of a human being. Most agencies require re-training and qualifications at firearms ranges with a 75%-80% proficiency threshold. Would marksmanship training become a bi-annual part of a teachers new continuing professional training requirement?

It is unlikely that an educator would go through this type of testing and training in the first place. It is even more unlikely for the teacher to draw and fire at another person, perhaps a student, a female, or a person of color. In school shootings, we have seen that young people are often the perpetrators. Studies have shown a reluctance of soldiers to shoot at another human being. These are soldiers. I can imagine the struggle that educators would have when confronted with having to shoot another person.

Police officers are trained to make quick decisions and use deadly force when all factors are present. It is one thing for a teacher to calmly say they will use a firearm in defense of themselves or other students, but it is quite a different story in reality.

Other factors include firearm accessibility. Will they be concealed carry? Will they be locked in a “readily accessible storage lock box?” Every officer knows the answer to the “quickly accessible” storage containers dilemma.

I understand, Joel, about the immediacy of teachers being on scene long before the police unit arrives, but I believe that the hesitation delay would nullify the advantages.

Teachers running around schools in civilian clothing, firearms in hand, will be prime targets to arriving units. In the heat of the moment, teachers may not be expected to ignore instincts to continue to pursue the perpetrator or to stop firing at them. It is a predictable tragedy. Shooting bystanders is a real possibility as well. As studies have shown, firearms in the home account for unintended consequences that include accidental discharges, stolen weapons and even suicides.

Will teachers be protected with a sort of qualified immunity if they make a mistake and shoot the wrong people or have an accidental discharge?

Teachers have a role in our schools but being an armed defender should not be an added requirement.

Joel Shults: Certainly, there are questions, Jim, about storage, liability, the ability of untrained persons to perform under pressure, and all of the dangers of firearms ownership and use. I think these can be overcome.

The mere arming of teachers who volunteer to carry would only be a part of a prevention/early response plan. As you know, police officers shoot with only a 30% accuracy in the real world, despite their training and stress inoculation. Street criminals using firearms don’t fare much worse (no concern for life, liability, policy, safety downrange, etc., to slow their decision-making), so we know that reflex shooting by a civilian at what would necessarily be close range might not be as messy as we think.

I am still perplexed by the urge to evacuate when students are safest behind a locked classroom door. If the only objective an armed teacher has is to keep an attacker on the other side of a locked door, that would address the greatest likelihood of ever having to fire a weapon – reasonably close range and framed by the doorway.

We’ve also seen the heroism of teachers, and even students and other staff, who have intervened and stopped or slowed attackers. What that proves, I think, is that the willing spirit and desire to protect children can only add positively to the equation. Not everyone will want to carry a gun but those who can, should. If the attacker wants to play whack-a-mole to find out what classrooms will offer deadly resistance, that’s a chance the shooter will have to take.

Jim Dudley: Joel, you present terrific anecdotal examples of heroism, but I would estimate that those done by non-sworn as rare occurrences, rather than the rule. Law enforcement officers undergo the aforementioned training and have experience and expertise. Still, the response does not always go as planned. We have seen some faulty judgment and tactics that may cause tragedies to result. I’m sorry to say the incidences of negative outcomes would occur as a result of universally arming teachers and educators.

Our best defense against these types of attacks is in prevention, not response. We need to have better situational awareness of those behaving erratically, making threats and amassing arsenals. We then need to be able to address them with threat assessments to those situations, rather than ignore or dismiss them. It also reinforces the need to have good, diligent school resource officers in schools with open and clear communication with students and faculty.

Joel Shults: Prevention is absolutely the priority and perhaps making potential shooters think twice about whether they are going to face a teacher with a gun can be a part of that prevention effort. When we imagine school staff with a firearm, we might envision a movie character version of Bruce Willis sneaking through the ductwork to take aim. But really all we have to do is to let a teacher who is willing and able to bear a firearm do so and be clear that their only responsibility is for their kids in their classroom. That limits the chaos that we fear from mistakes and misfires and zeroes in on the greatest point of vulnerability. We need not keep our soft targets soft.

[ad_2]

Source link