Opinion: Why America keeps re-living the 1990s

[ad_1]

Editor’s Note: Nicole Hemmer is an associate professor of history and director of the Carolyn T. and Robert M. Rogers Center for the Study of the Presidency at Vanderbilt University. She is the author of “Messengers of the Right: Conservative Media and the Transformation of American Politics” and the forthcoming “Partisans: The Conservative Revolutionaries Who Remade American Politics in the 1990s.” She cohosts the history podcasts “Past Present” and “This Day in Esoteric Political History.” The views expressed in this commentary are her own. View more opinion on CNN.

CNN

—

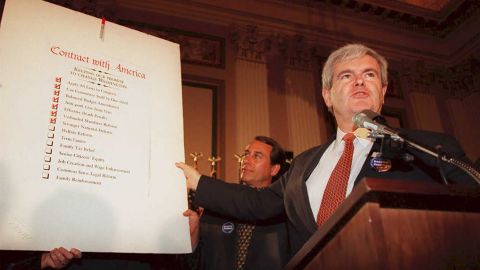

Last week, the January 6 committee announced they had sent a letter to former Republican Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich, asking him to testify about his role in promoting the Trump administration’s efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election. The committee, among other points, claimed Gingrich had been involved in efforts to put forward fake electors during the election certification. And while the January 6 committee draws connections between Gingrich and election denialism, Republican leader Kevin McCarthy is attempting to emulate the former Speaker, launching the “Commitment to America,” a sort of Contract-with-America redux, in his effort to secure a Republican majority in the midterm elections.

The return of Gingrich, one of the most prominent political figures of the 1990s, to the thick of one of the biggest political stories of the 21st century is no coincidence. As one of the leading purveyors of polarization in the 1990s, Gingrich helped to create the political environment in which former President Donald Trump would later flourish.

In his heyday as Speaker, Gingrich was arguably the most visible manifestation of this movement, but it went far beyond Washington. From political entertainment to militias to media-driven conspiracy theories, a number of developments in US politics and culture in the 1990s set the stage for the radicalized and anti-democratic right of the present. In doing so, they represented a sharp turn away from the politics of Ronald Reagan.

Focused on building sizable majorities, Reagan appealed to White voters by foregrounding popular policies and developing an upbeat persona. But in the decade that followed his presidency, the right closed ranks, tearing down the big tent and working to polarize the electorate. In the process, they developed the right-wing ecosystem – and democratic skepticism – that shapes US politics today.

Three moments in particular stand out that can help us better understand the current political crisis – and by extension, illuminate how we might find a different path forward. Not all carry the same weight, but each helps us better understand how the politics of the 1990s helped erode the boundaries between extreme and mainstream politics on the right.

One day in 1994, GOP Indiana Rep. Dan Burton carried a .38-caliber pistol and a melon – likely a cantaloupe – into his backyard. He then took aim and shot the melon, a story he recounted on the floor of the House in early August that year.

The experiment, he claimed, proved that Vince Foster, a deputy White House Counsel in the Clinton administration who had died by suicide a year earlier, could not have killed himself. He must have been murdered. And the White House must have been involved in the cover-up.

Shooting fruit was not the only way Burton spread conspiracies about then-President Bill Clinton and First Lady Hillary Clinton during his time in Congress. That same year, he promoted “The Clinton Chronicles” to his colleagues, all of whom received a gratis copy of the full-length, documentary-style conspiracy video.

The video, put out by a group calling itself Citizens for Honest Government and distributed by right-wing preacher Jerry Falwell, was a lurid tale of corruption and criminality centered on the governor’s house in Arkansas, where Bill Clinton served before ascending to the White House.

Several of the people in the video had been paid; others later retracted their stories. But the video bore fruit in the Clinton years. It helped fuel the so-called “Clinton Body Count” conspiracy theory, still wildly popular on the right. And it taught Republicans that there was potent political possibility in weaponizing even the most outlandish conspiracies: the House Banking Committee spent two years and millions of dollars investigating the claims in “The Clinton Chronicles.” They found no basis for the video’s claims, but the air of scandal their investigations generated helped define the Clinton presidency – and set a precedent for dealing with every Democratic president who followed.

In 1993, Comedy Central – then a fledgling cable network attempting to establish its identity on a rapidly expanding television dial – struck gold with the new show “Politically Incorrect” hosted by Bill Maher. Maher wanted a show that “made controversy funny,” as he put it.

Both humor and controversy were key to the show’s popularity. As its name indicated, panelists who appeared on “Politically Incorrect” used comedy to say the things they believed people couldn’t, or shouldn’t, say. On the “Politically Incorrect” stage, a unique style of genre-bending late-night TV – fueled by brash, jokey right-wing punditry – was born.

Young conservative commentators like Laura Ingraham and Ann Coulter were a perfect fit for the show, taking advantage of the comedy stage to offer up especially provocative takes that were met with a mix of gasps and laughter. As part of the show’s roster of panelists, they often mingled with actors and comedians, each drafting off the others’ professional acumen as the stars tried their hand at punditry and the pundits cracked wise.

The show’s controversy-as-humor approach not only laundered ideas, but also reputations. In March 1995, the panel featured Daryl Gates, the former chief of police in Los Angeles who resigned after the 1992 uprisings in Los Angeles brought intense focus on the LAPD’s history of racist brutality. He appeared on the panel with high-powered stars: Jay Leno, George Clooney and Gabrielle Carteris from “Beverly Hills, 90210.”

During the show, Maher questioned him not about the abuses that took place under his watch but about whether America had become too soft on crime. At one point, when Leno made a jab at Maher, Maher turned to Gates and said, “Get me a baton.” The audience erupted in laughter.

It was a moment that captured the crucial political work that the comedy show did: playing police brutality for laughs while presenting Gates not as a disgraced former official but an expert on criminology. Concerns about excess force were reclassified as just another manifestation of political correctness. In a decade when the walls between politics and entertainment were thinning, Gates’s appearance showed just how powerful the blending of those two worlds could be.

Several months after Congress passed the federal assault weapons ban, the president of the National Rifle Association sent out a six-page letter to members of the group. Railing against the lawmakers who approved the bill, then-NRA executive vice president (later CEO) Wayne LaPierre fumed, “It doesn’t matter to them that the semi-auto ban gives jack-booted government thugs more power to take away our constitutional rights, break in our doors, seize our guns, destroy our property, and even injure or kill us.” In case “jack-booted government thugs” was too subtle, he went on to describe federal agents in “Nazi bucket helmets and black storm trooper uniforms.”

The letter went out in early April 1995. On April 19, domestic terrorists detonated a bomb at a federal building in Oklahoma City, killing 168 people. LaPierre and the NRA strenuously denied any direct connection between the two events.

The NRA had been building power throughout the earlier 1990s, attempting to battle back legislation meant to curb gun violence in the US and drawing energy from the burgeoning militia movement’s anti-government conspiracy theories following the violent events at Ruby Ridge and Waco, as journalists noted at the time and as historians such as Kathleen Belew have more recently addressed.

But the timing of a letter demonizing federal agents coming just days before the bombing of a federal building jeopardized the organization’s standing. In response to public anger at the NRA’s antigovernment rhetoric, LaPierre went on NBC’s “Meet the Press” to defend his statements. “These words are not far, in fact they are a pretty close description of what’s happening in the real world,” he said on the Sunday news show.

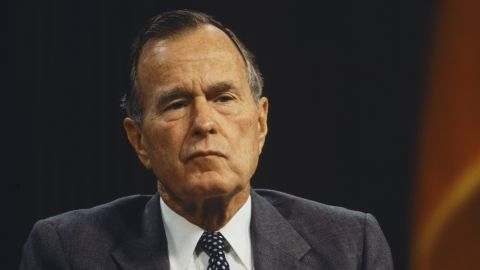

That was the last straw for one former president. After LaPierre’s comments, George H.W. Bush resigned his lifetime membership in the NRA.

The organization did not, however, lose power. Within the Republican Party, its influence grew rapidly over the years that followed, even as it continued to embrace extreme and conspiratorial rhetoric.

Still, Bush’s resignation mattered. It drew a line between the anti-government rhetoric used to sell deregulation and tax cuts and the anti-government rhetoric used to foment violence against the state. It suggested Republicans had a responsibility to police rather than absorb extremist elements.

At a moment when Americans are struggling to understand how extremist politics became mainstream in the US, it’s useful to remember that there was a time when a former Republican president denounced rather than embraced comparisons between federal agents and Nazi stormtroopers. It’s also useful to note the limits of that denunciation even at that time: the right was ready to embrace extremism, even as members of their own party sounded the alarm.

The echoes bouncing between these stories and current-day politics are not a case of history repeating itself. Rather, they are a reminder that our current political crisis is a consequence of decisions made in the 1990s to embrace controversy, conspiracy, and extremism. As such, it is also a reminder that the current crisis is an outgrowth of institutions as well as personalities, and lasting change will only result from deep-rooted reform of those institutions.

[ad_2]

Source link