The racist 1890 law that’s still blocking thousands of Black Americans from voting | US voting rights

[ad_1]

The Mississippi officials met in the heat of summer with a singular goal in mind: stopping Black people from voting.

“We came here to exclude the Negro,” said the convention’s president. “Nothing short of this will answer.”

This conclave took place in 1890. But remarkably, approximately 130 years later, the laws they came up with are still blocking nearly 16% of Mississippi’s Black voting-age population from casting a ballot.

The US stands alone as one of the few advanced countries that allow people convicted of felonies to be blocked from voting after they leave prison. The policy in Mississippi underscores how these laws, rooted in the explicit racism of the Jim Crow south, continue to have discriminatory consequences today.

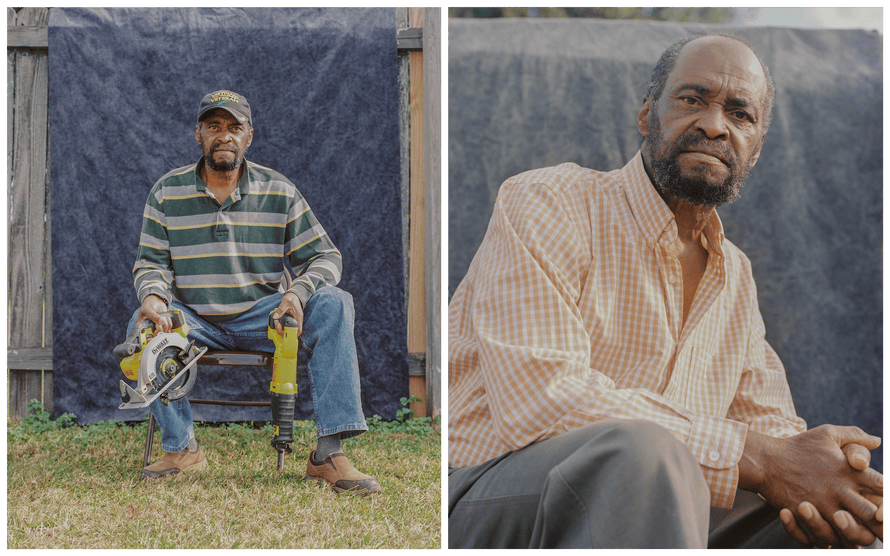

One of those affected is Roy Harness, a 67-year-old social worker, who may never be able to vote because of a crime committed decades ago.

In the mid-1980s, he was convicted of forgery after he ran up a debt to a drug dealer and cashed a series of fake checks. He spent nearly two years in prison and hasn’t been back since.

In recent years, Harness, who is also an army veteran, has been on a new path. He enrolled in college when he was 55 and got his bachelor’s degree when he was 63. He got a master’s degree in 2019. Now a full-time social worker, Harness keeps a shelf behind his desk filled with awards and accomplishments – a reminder to his clients of all they can accomplish.

In 2013, he tried to register during a voter registration drive at his college, but saw on a pamphlet that forgery, the crime he had been convicted of decades earlier, was a disenfranchising crime in Mississippi.

“It makes me feel bad. I’ve served my country, nation … got a degree and [I] still can’t vote, no matter what you do to prove yourself,” he said.

Mississippi also makes it nearly impossible for anyone convicted of a felony to get their voting rights back. Fewer than 200 people have succeeded in restoring their voting rights in the last quarter-century, the Guardian can reveal, based on newly obtained data.

Now, Harness is involved in a new effort to change Mississippi’s law.

After slavery ended in Mississippi, following the US civil war, newly enfranchised Black voters in the state were beginning to wield political power. In 1870, Mississippi sent Hiram Revels to the US Senate, the first Black person to serve in the body.

By 1890, the delegates who gathered for a constitutional convention in Jackson, the state capital, were determined to blunt this trend.

They faced a significant roadblock to their racist goal. The new 15th amendment to the US constitution explicitly prohibited states from preventing people from voting based on their race. And so the delegates came up with a plan that would effectively prevent Black people from voting without explicitly saying that was their intent.

The delegates enacted a poll tax and literacy tests, measures that would become widespread across the south, as a way of keeping people from voting. But they also enacted a provision that disqualified people convicted of specific felonies from voting. The crimes they picked were those they believed, based on prejudices, Black people were more likely to commit. Bribery, burglary, theft, arson, bigamy and embezzlement were among the crimes that would cause someone to lose their voting rights. Robbery and murder were not.

Mississippi continues to see the legacy of its efforts to shut Black voters out of the political process today. It has one of the highest concentrations of Black people in the country, yet has not elected a Black person to statewide office in well over a century. It was among the states with the lowest voter turnout in the US in 2020.

Even though Black Mississippians comprise about one-third of eligible voters in the state, they account for more than half of the 235,152 people who can’t vote in the state because of a felony conviction, according to an estimate by the Sentencing Project, a criminal justice non-profit. Overall, more than one in 10 citizens of voting age can’t cast a ballot in Mississippi because of a felony conviction – the highest rate of disfranchisement in the US.

And it is astonishingly difficult for those affected to get their right to vote restored.

To vote again, people with disqualifying felonies in Mississippi must first convince a lawmaker to introduce a bill in the legislature on their behalf to restore their voting rights. In other words, they need their own, individualized piece of law.

The bill must then pass both chambers of the legislature by two-thirds vote and be approved by the governor. Mississippi is the only state in the country where people convicted of felonies need to go through the legislature to get their voting rights back, said Christopher Uggen, a professor at the University of Minnesota who studies felon disfranchisement.

The only other path to get one’s voting rights back is a gubernatorial pardon, which hasn’t been granted in Mississippi in nearly a decade.

The process is the same one the delegates spelled out during the 1890 racist constitutional convention, where the felony disqualification rule was created. It was included as a safeguard to ensure that well-connected white Mississippians who committed one of the disenfranchising crimes had a way of gaining their voting rights back.

Mississippi does not keep track of how many people successfully get their voting rights restored each year. But data compiled by Blake Feldman, a criminal justice researcher in Mississippi, shows it’s almost no one. Feldman began tallying the data in 2018 for the Southern Poverty Law Center, and has continued to track it since.

Since 1997, an average of about seven people have been successful each year. In the 2021 legislative session, just two people made it through the process.

There are no posted instructions anywhere online, said Hannah Williams, a research and policy analyst at MS Votes, a non-profit that works to expand voter access. Applicants must submit a paper form – there is no online option – to their lawmaker and convince them to vouch for them. After that, their fate is in the hands of lawmakers, who can reject an application for any reason.

“There really isn’t a way to guarantee anything because the process doesn’t really make sense. There’s no information. You can’t go to a website. And to be honest, you can’t even call the capitol to get information, because they don’t really know what the process is,” she said.

“Unless you know somebody that knows somebody that knows somebody who has their ear to the floor, you don’t know when you have to turn these applications in,” she added.

Nick Bain, a Republican who chairs the Mississippi House judiciary committee, which oversees the bills for rights restoration, acknowledged the process was “convoluted”. Both chambers can set whatever criteria they want people to meet before they restore someone’s voting rights. Those criteria, which are not posted publicly, do not have to agree.

“I do believe it’s patently unfair the way that we do the process. And maybe as a Republican, that may not be the Republican thinking on that,” he said. “We have a problem with consistency. The process, it’s by no means perfect. By no means is it efficient … But right now it’s the only process that we have.”

While the law today continues to disproportionately affect African Americans, white Mississippians are affected too. Dennis Hopkins, a 46-year-old maintenance supervisor from Potts Camp, Mississippi, was convicted of grand larceny as a teenager in the 1990s, released from prison in 2001, and hasn’t been able to vote since. Because he was convicted of a felony when he was a teenager, he’s never been able to vote in his life.

Even though he has raised nine children (he’s adopted several), become a local fire chief, and coached many school sports teams with hundreds of kids, he can’t vote.

“I’m thinking ‘you sentenced me to four years in prison and you’re giving me a life sentence,’” he said. “I feel like I’m a branded man and I’m not equal to everybody else.”

Harness and Hopkins are now the lead plaintiffs in two separate high-stakes federal lawsuits challenging Mississippi’s felon disfranchisement laws.

One suit argues that the list of original disqualifying crimes unconstitutionally targeted Black people and therefore should be struck down. The second, filed by the Southern Poverty Law Center in 2018, also challenges the Mississippi policy and takes aim at the arcane restoration process.

“The process is fundamentally arbitrary and inherently susceptible to discrimination,” lawyers wrote. “There is no oversight of any kind to ensure that legislators do not exercise their discretion to vote against a proposed suffrage bill on the basis of an individual’s race, religion, or political leanings.”

Even though the core of Mississippi’s policy remains what was drafted during the 1890 convention, lawyers for the state have argued its discriminatory taint has been removed. There have been small tweaks to the law; voters chose to remove burglary disenfranchising crime in 1950 and added murder and rape in 1968.

In February, the US court of appeals for the 5th circuit upheld Mississippi’s policy, writing that 20th-century tweaks to the law removed the discrimination written into it in 1890. But the court later agreed to rehear the case, and there were oral arguments in September. A decision is expected in the coming months.

In late October, both Harness and Hopkins traveled to the state capitol and appeared before a panel of lawmakers. They were there for a hearing convened by Bain, who wanted to explore new ways to fix the process for getting voting rights back.

At the end of the hearing, one of the lawmakers approached Hopkins and offered to file a rights restoration bill on his behalf. Hopkins was unaware the process was even a possibility – he had been told there was no way for him to get his voting rights back. Still, he refused.

“That’s not gonna help everyone else. I told them no – I’d prefer not to do that,” he said.

“I tell my kids how important the vote is … it shames me to tell them I can’t vote and here is why,” he said. “I know there’s a lot of people who say, “my vote doesn’t count. Well I beg to differ. It does count.”

[ad_2]

Source link