Do Textbooks Shape Attitudes Toward War? Narrative ‘Images’ and Implicit Social Cognition

[ad_1]

To explore the relationship between history education and attitudes to war, narrative primes about World War II were read by 20 undergraduate students at California State University, Fresno. Afterwards, in the course of experimental interviews, participants responded to news of a hypothetical terrorist attack and shared policy solutions and opinions about war. Analysis revealed that interview responses were patterned by narrative. While readers of an ‘enemy’ narrative conveyed feelings of loss, aggressive policies, and war support, readers of ‘ally’ and ‘imperialist’ narratives were less alarmed by the attack and less supportive of war. Instead, they proposed using ‘talk’ to ‘understand’ both sides of the conflict. Political views had little effect and ‘defaults’ to war support were witnessed. In the exploration of possible mechanisms, authoritarianism and the cognitive literatures of prospect theory, image theory, schemata, and the dual process model were considered. To explain why narratives realistic about war were less related to perceptions of loss, it was suggested that loss may be experienced relative to the perceived intentions of salient social actors. Such an interpretation modifies prospect theory with image theory. The study should sensitize educators and policymakers to the consequences of history education for implicit bias and attitude formation.

Formal education is problematic: necessary for industrialized societies to reproduce themselves, and yet emancipatory, capable of diminishing allegiance to any one model of society. Owing to this fundamental paradox, the 19th century saw the first truly public education systems alongside organized efforts to control them: accordingly, teacher training, learning objectives, and textbooks were standardized. It was assumed many boys would pursue military careers, so militarized history and geography were prominent in curricula. These textbooks were not neutral: they described the citizens of other nations in threatening terms (Marsden 2000b). Educators who opposed the militaristic curricula were outliers (Elmerslö and Lindmark 2010; Marsden 2000a, 2000b).

Following the First World War, education for ‘international understanding’—in effect, peace education—became mainstream, and organizations devoted to peace emerged (Marsden 2000a, 2000b). Among their activities, the National Counsel for the Prevention of War conducted research into textbook content and discovered that discussions of war outnumbered accounts of humanitarian deeds and peacetime events (Marsden 2000b). Concerned about the ramifications for international relations, international bodies, including the League of Nations, attempted to leverage textbook reform (Marsden 2000a, 2000b; Siegel and Harjes 2012). The Second World War disrupted the process, but in some countries, efforts resumed later (see Siegel and Harjes 2012 for the development of a joint Franco-German textbook). In the United States, concern dropped off. Although voices remain, they are no longer mainstream (Scott 2009).

Because states are not, and have never been indifferent to academic outcomes, public education cannot be viewed as merely a mandatory period of formal instruction. To the contrary, public education aims at the accomplishment of entwined social, economic, political, and military power. To the extent states do not explicitly pursue peace, public education prepares for war.

To understand how cultural media such as historical narrative accounts relate to political attitudes, a more sophisticated comprehension of cognitive processes is necessary. A data driven field encompassing psychology, neurology, and even computer sciences, the cognitive sciences aim to reveal processes behind learning, decision-making, attention and inattention. Some of this research addresses war support.

In recent decades, the idea that cognition is organized in dual processes—implicit and explicit—has become a dominant model among researchers (Ksiazkiewicz and Hedrick 2013). The model is part of the cognitive miser paradigm, which observes that cognition, like other physiological functions, is taxing; consequently, humans have evolved neurological arrangements that optimize the efficient use of limited resources (Ferguson and Zayas 2009; Kahneman 2011). As a result, individuals bring varying degrees of scrutiny to different tasks, based on perceived challenge and risk. With such a system in place, most stimuli can be handled on the basis of learned or automatic implicit functions, and energy is conserved for tasks requiring greater care.

In general, implicit processes suffice the act of reading: one cannot fail to recognize a written word in any language one knows. Likewise, implicit processes are the domain of stereotypes, biases, detecting hostility, and feeling fear (Kahneman 2011), making them party to approach-avoidance motivation (Elliot and Covington 2011; Ferguson and Zayas 2009). In this vein, implicit processes render human consciousness vulnerable to framing effects—the structuring of decision-making from without by rhetorical means—as well as primes—environmental cues (discourse or objects) that make particular ideas salient and influence behavior (Kahneman 2011).

Prospect theory, a theory of layman risk analysis, is consonant with the dual process approach and explicit about the dangers posed by such a processing system. The theory highlights how considerations of loss versus gain, framed from a ‘reference point’, bias decision-making: people prefer gains which are certain, however, they also tend to overvalue prospective (or potential) losses. The theory thus makes predictions about the conditions likely to promote risky behavior. The ‘Asian disease’ experiment is a well-known example that demonstrates the importance of the theory for policy debates. In one experimental condition, participants preferred a public health policy simply because it provided certainty. All policy options were described in terms of lives saved, and participants opted for the policy in which lives were most certain to be saved. In a separate ‘loss’ condition, all policy options were framed as loss, and in this condition, participants preferred the riskiest policy option. Substantively, however, the risks described by the riskiest policies were equivalent between the two conditions (Tversky and Kahneman 1981). Said another way: in the ‘loss’ condition, participants had been primed in terms of loss, and the primed sensation structured subsequent behavior. In spite of themselves, loss-conditioned study participants made the riskiest choices (Kahneman 2011).

Thanks to its predictive power and real-world applications, prospect theoretic research has pierced disciplinary confines, producing a cognitive field within the study of international relations. Thus, it has been found that the use of loss frames in mass media functions to legitimize interventions and wars (Perla 2011). Advocates for peace, however, can also use loss frames to their advantage. The key is the reference point. When Gayer and colleagues (2009) framed the policies of Israel as a source of loss—rather than the Palestinian minority—they succeeded in transforming opinions on a polarizing subject.

Prospect theory has an important shortcoming. Perceptions and consequently decisions flow from a reference point; how the reference point is determined, however, is untheorized (Levy 1997, 2003; Perla 2011). Seeking to account for the theory’s gap and explain support for U.S. military interventions, Perla (2011) has proposed a ‘Framing Theory of Policy Objectives’. According to the model, reference points follow mediatized debates. As one frame becomes dominant among media elites, a point of reference is established from which to define a situation as one of loss or gain, and public opinion falls into line. The work provides further evidence that public opinion is attuned to suggestions of gain and loss, in addition to elite cues. It does not illuminate how such a risk discourse emerges in the first place. That is, the Framing Theory of Policy Objectives takes for granted perceptual processes themselves, and how these are social in nature, even when the object of evaluation is overseas.

Outside prospect theoretic research, other approaches make social judgments the center of their analyses. Impression formation, an early approach within the emerging field of social cognition, deals with how people form seemingly complete impressions based on incomplete information. Image theory, a cognitive approach within the discipline of international relations, sees relations between nations as interactions between perceived archetypal ‘images’. Although both fields date to around midcentury, they developed independently. Serendipitously, they make analogous assumptions about the considerations that weigh on decisionmakers. Impression formation came first: it was Asch (1946) who observed that perceptions of ‘warmth’ loom large when forming opinions of others. Further, in language prescient of image theory, he affirmed that ‘To know a person is to have a grasp of a particular structure’ (1946, 283, emphasis added). Since Asch, a body of social cognition work has validated and elaborated this basic intuition. In addition to ‘warmth’ (or ‘morality’; see Wojciszke 2005), perceived ‘competence’ also weighs on social judgments. Such evaluations are automatic (Wojciszke 2005) and universal (Fiske, Cuddy, and Glick 2007); ostensibly, because ‘warmth’ provides information about the intentions of social actors whereas ‘competence’ concerns executive abilities.

Strikingly, image theory—the field with cognitive aspirations within the study of international relations—also emphasizes dimensions akin to warmth and competence. The approach was pioneered by Boulding (1956, 1959) who argued that environments are composed of ‘images’ that reflect the existential considerations of nations. Today, it is generally agreed that these considerations have to do with the perceived power, cultural status, and goal (in)compatibility of an ‘Other’ nation, and a handful of outgroup images have come through this research reflecting different combinations of those dimensions. The most universally recognized are the enemy, ally, imperialist, barbarian, and colony images.

Experimental manipulations confirm that people, including children (Oppenheimer 2005) and college students (Bilali 2010; Alexander, Brewer, and Herrmann 1999; Herrmann et al. 1997) recognize images. Multiple studies show that emotions drive image choice (Herrmann et al. 1997; Alexander, Brewer, and Herrmann 1999; Bilali 2010). Eicher and colleagues (2013) find that emotions also follow from images and that images emerge as a result of the structure of group relations. In turn, images predict behavioral tendencies. Enemies are viewed as physically and culturally powerful and as possessing no goals or values in common with allies (Alexander, Brewer, and Herrmann 1999; Eicher, Pratto, and Wilhelm 2013). Luostarinen (1989) has suggested that enemy images constitute a kind of mental military preparedness: one expects to be attacked by enemies and prepares to evade and/or retaliate. By contrast, imperialists are seen as using cultural power to achieve dominance (Bilali 2010; Eicher, Pratto, and Wilhelm 2013), and perceiving such an image is related to the desire to resist (Bilali 2010). Allies can be similar to enemies and imperialists in terms of military power and cultural prestige, but they are seen as goal-compatible, which promotes cooperation (Alexander, Brewer, and Herrmann 1999; Eicher, Pratto, and Wilhelm 2013). Fittingly, images have been studied in terms of approach and avoidance motivation (Bilali 2010).

Herrmann and colleagues (1997) as well as Murray and Cowden (1999) point out that images are schemata, or mental models that aid perception, memory, and which are even involved in attitude change. Generally, schemata are considered a micro topic, since they are studied relative to individuals. However, studies have unfolded on two levels. So-called ‘macrocognitive’ schemata research is deemed ‘macro’ for its interest in concepts or structures, rather than processes. Experimental research has routinely demonstrated the tendency to complete or systematically misconstrue patterns on the basis of culturally relevant or irrelevant stimuli, confirming schemata exist (Rice 1980). Meanwhile, from the 1980s forward, a statistical, ‘microcognitive’ orientation has emerged in the floodplain between cognitive and computer sciences (see Rumelhart, McClelland, and PDP Research Group 1986). This field emphasizes process, and one approach is ‘Parallel distributed processing’, also known as ‘connectionism’. From this research, it has been concluded that schemata possess key attributes. Among them, schemata are activated by ‘minimal input’ and prone to ‘pattern completion’ (D’Andrade 1995; D’Andrade and Strauss 1992; Rumelhart, McClelland, and PDP Research Group 1986; Smith 1996). That is, once minimal input is perceived and the schema is activated, people tend to provide additional information, completing the schema.

Thus, schemata are resistant to change (Smith 1996). And yet, change is possible. In the face of competing stimuli, schemata adapt, demonstrating flexibility or ‘constraint’ (Rumelhart, McClelland, and PDP Research Group 1986). For comparison, computers were traditionally built as ‘serial symbolic processors’ (Rumelhart, McClelland, and PDP Research Group 1986; D’Andrade 1995), making them inflexible. The brain, however, is a flexible problem solver. Unable to manage constraint, computers crash. Human brains manage constraint by deriving unique solutions that harmonize differing inputs.

These differences in processing style make attitude change possible, even in the context of war. In the first days and weeks of the Persian Gulf War, Spellman, Ullman, and Holyoak (1993) used a model based on the principle of constraint satisfaction to map the relationship between attitudes and new information. Detecting bidirectional relationships between direct and indirect attitudes, the authors conclude that cognitive structures are complex and interactive. Individuals are driven not merely to maintain cognitive consistency, but capable of generating coherence, a kind of maximal consistency that involves constraint in all cognitions.

Nearly a century ago, Fromm (1941) suggested that the chronic experience of economic threat from the end of the Middle Ages forward was responsible for the development of ‘authoritarian’ attitudes in Germany. The construct was then popularized by The Authoritarian Personality, an account of the first efforts to operationalize and study the concept empirically (Adorno et al. 1950). The authors argued that authoritarianism is a personality syndrome that can be measured by the f-scale (‘f’ for fascism), but the approach did not hold up (Martin 2001).

More recently, Duckitt (1989) set the field on its current path. In a landmark paper, Duckitt defined authoritarianism as ‘the normatively held concept of the appropriate relationship between group and individual member, determined primarily by the intensity of group identification and consequent strain toward cohesion’ (1989, 63). Accordingly, authoritarianism consisted in interpersonal values and behaviors, and possibly formed a distinct attitude—a conceptualization that restored threats to the study of authoritarianism and made the field truly social for the first time. Following Duckitt, a growing proportion of work accounts for group cognition and/or perceived threats in order to explain authoritarian attitudes and behaviors (see Hetherington and Weiler 2009; Lavine, Lodge, and Freitas 2005; Stellmacher and Petzel 2005; Stenner 2005). Mirroring the trend in cognitive studies toward fewer and larger constructs, the current field favors simpler, more dynamic, and processual conceptions. Stenner’s (2005) definition is especially efficient: authoritarianism is a ‘need’ for order (conformity) in the face of ‘normative’ cultural threats and a propensity to endorse punitive force in order to achieve it.

Authoritarian threat response is well established empirically and germane to the psychological study of war support (Hetherington and Suhay 2011). On the basis of the new approaches, it has been found that authoritarianism is a normal attitude in the United States that reveals itself dynamically under conditions of threat (Cizmar et al. 2014; Hetherington and Suhay 2011; Hetherington and Weiler 2009; Stenner 2005). However, some types of threats reduce the impact of authoritarianism. Stenner (2005) finds that ‘personal’ threats (defined as knowledge of the distress of others) decrease authoritarian intolerance and punitiveness.

Each of these findings begs another question. If the authoritarian attitude and behavioral pattern exists, is there an opposing attitude and behavioral set? As long as the concept of has been studied, this issue has been neglected (Feldman and Stenner 1997; Greenstein 1965; Hetherington and Weiler 2010; Martin 2001; Stenner 2005). Some work theorizes ‘anti-’ (Perrin 2005) or ‘non’-authoritarianism (Doty, Peterson, and Winter 1991; Hetherington and Suhay 2011; Hetherington and Weiler 2009; Lavine, Lodge, and Freitas 2005); the attributes distinguishing authoritarianism from -anti and -non, however, are typically taken for granted. Stenner (2005) uses the label ‘libertarian’; however, it is questionable whether the libertarian attitude tapped by her survey is a counter authoritarian attitude, as individuals expressed more concern with the notion of top-down control than with violence—clearly, a fundamental parameter for identifying authoritarianism.

Much earlier theoretical discussions spoke of ‘democratic character’ (Lasswell 1951; see also Melby 2006, a 1936 reprint). Effectively, these approaches described empathy, and research has validated those inklings. Bizumic and colleagues (2013) find that empathy predicts attitudes and activities supportive of peace, whereas authoritarianism, preoccupation with strength and order, and less personal distress about war anticipate attitudes and activities supportive of war. People act on empathy when they feel capable of making a difference. People fail to act empathetically when they feel powerless to do so (Aronson 2011).

To examine the impact of textbook narratives on attitudes to war, 20 undergraduate students taking U.S. history classes at California State University, Fresno were exposed to thematically distinct ‘narrative primes’ about the Second World War. The construction of distinct primes was achieved by shaping each narrative around a particular social ‘image’. In accordance with image theory, the approach yielded an enemy-, ally-, and imperialist narrative, respectively.

The ‘enemy’ narrative was derived from a textbook used in a Fresno, CA-area high school, The Americans (Danzer et al. 2006) because it privileged the hostile intentions of foreign dictators in explanations of the conflict. Although the adapted text (like all narrative primes) was limited to three single-spaced pages, a high proportion of language was true to the original source material. Deviations were therefore few and served to transition the narrative between different events of the war while maintaining the original tone of the text. As a result, the reading focused on leaders and battles, but not in a particularly realistic way. Instead of actually discussing human casualties, the text relied on metonyms: ‘planes’, ‘ships’, and even the names of cities alluded to the loss of human life. FDR, Hitler, and others transformed into dramatic characters, and complexity was almost nonexistent. This lack of complexity made the enemy orientation even stronger, as no other conflicts competed for readers’ attention. Concluding the passage, language about the American occupation and Westernization of Japan absolved Japan of enemy status. Indirectly, the narrative implied that war is necessary to deal with enemies.

To counterpoint the emphasis on enemies, an ‘ally’ narrative prime drew on excerpts from The ‘Good War’, a collection of interviews gathered by Studs Terkel (1985). Without blaming foreign nations, the ally narrative focused on people and the everyday wartime realities: the sorrow of an American prisoner of war who lost friends and thousands of comrades on the Bataan Death March; the anger of a nurse over the stigmatization of disfigured soldiers; the disappointment of a woman who lost career and family and cared for children during the Battle of Britain. The experiences were diverse, but they shared a core: for each of these individuals, the foreign enemy was not the immediate or only problem. The immediate problem was the war itself, which contradicted the values, the humanity, and the life goals of the people caught up in it.

Finally, an ‘imperialist’ narrative—created by merging the scholarly accounts of Rigberg (1991) and Zinn (2010)—took a related, but separate tack. Contrasting both the enemy- and ally narratives, the resultant text centered economic interests and was explicit about exploitation and moral hypocrisy on the part of the Allies. Distinguishing between ‘underlying’ and ‘precipitating’ causes of conflict, the text emphasized the former, crediting competing imperialisms in Asia—Western as well as Japanese—for the U.S. sanctions that led Japan to attack Pearl Harbor. Accordingly, the Roosevelt Administration anticipated the assault and contemplated in advance how to justify the situation to the American people. Further on, the text described rifts between U.S. and British diplomats, who proposed war strategies based on their competing economic interests. Similar motivations structured the end of the war in the Pacific: the text argued with evidence that nuclear bombs served to obviate a prior agreement with the Soviet Union regarding occupation of the defeated country. Drawing to a close, the narrative recalled the satisfaction of U.S. business elites who hoped for a ‘permanent war economy’. It ended presaging the social ‘rebellions’ of the 1960s, since gender-, race-, and class-based inequalities were not resolved by the war.

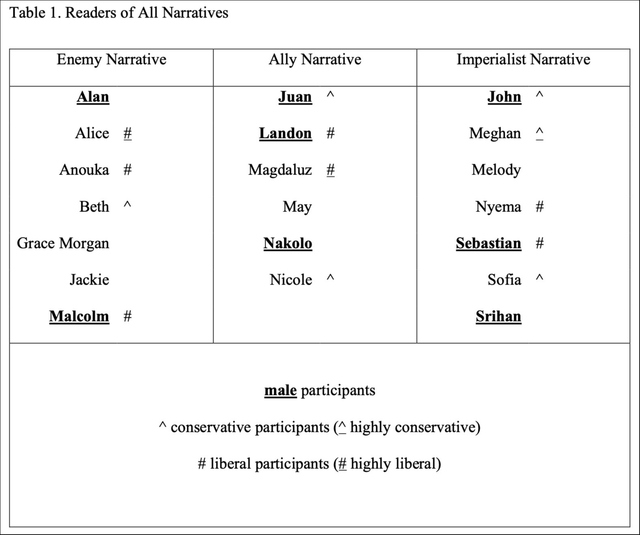

Prior to participation, readers were asked to supply basic demographic information, including political orientation and preferred news sources. To ensure readers from different backgrounds had the opportunity to experience each narrative, care was taken to stratify the sample as much as possible. Political preferences could not be known until after the experiment had concluded; nevertheless, in the final analysis, individuals were well distributed between narratives on the basis of their respective views (see Fig. 1).

In the interviews that followed, participants discussed impressions of the narratives, shared personal recollections of high school history curricula, and indicated what they understood ‘economic globalization’ to mean. Next, they shared personal reactions and policies Congress ‘should’ put in place in response to a ‘violent attack on a financial center in a major U.S. city by a non-U.S. group organized in opposition to global economic inequality in which elites profit at the expense of others’. Intentionally, I did not use the term ‘terrorist’ and avoided it in discussions (many participants used the term themselves). Following each question, I heard participants’ responses without interrupting. If a participant voiced a policy without indicating an underlying rationale, they were asked to elaborate. If the participant exhausted their policy ideas while excluding the military option, only then were they asked if they would consider such an approach. Afterwards, participants were asked whether war solves problems.

After the interviews were recorded and transcribed, descriptive codes reflecting interview questions isolated responses for analysis. Analytic codes, such as ‘loss’ or an interest in ‘understanding’, were generated subsequently, based on the patterns that emerged within and between the first set of codes. While differences did arise between readers of ally- and imperialist narratives, they were small. Consequently, these readers were analyzed as one group comprising 13 individuals. Seven individuals read the opposing ‘enemy’ narrative. Since no patterns emerged regarding participants’ stated high school experiences or their (mostly low) awareness of economic globalization, these questions were excluded from the analysis.

Faced with the hypothetical scenario, all seven readers of the enemy narrative expressed a deep sense of loss. This was articulated in terms of assumptions that the scale of the attack, and/or its impact, had been significant. Three out of seven (Anouka, Grace Morgan, Jackie) conveyed fear that additional attacks were forthcoming. In particular, Alan and Alice assumed the attack would have a significant effect on the global economy. Malcolm, although he was the only reader of an enemy narrative to oppose war in the later phase of the interview, perceived both a ‘terrible’ loss of life as well as a ‘tremendous’ economic impact. Five readers ignored the possibility that life experiences may have related to the attackers’ aims and beliefs.

Loss was not experienced by ally- and imperialist readers in the same way it was experienced by readers of the enemy narrative. While five readers expressed alarm (two readers of the ally narrative: May, Nakolo; three readers of the imperialist narrative: Nyema, Sofia, Srihan), it was of a mixed type. One reader was alarmed by the behavior of U.S. elites, instead of the attack (Nyema). Of the four who were alarmed by the attack, only May feared further attacks, and only Srihan made explicit assumptions about scale. The sole international student in the study, Srihan imagined the impact in Sri Lanka would be ‘horrible’. Explaining his alarm, he stated that corporations play an important role in the economy of his country.

A clearer pattern emerged regarding the perceived scale of the attack. Ten out of the 13 implied or explicitly stated that the scale of the attack had been small, or did not address scale at all. (That is, some alarmed readers did not allude to scale: May, Nyema, Sofia.) In the words of Melody, the attack ‘wasn’t as big as other events that have happened’. Instead of loss or fear, many expressed sympathy for the individuals they had read about and suggested that life conditions motivated the attackers, including Srihan.

Prompted by the idea of an attack on a U.S. financial center, six out of seven readers of the enemy narrative were open to declaring war. Three explicitly volunteered U.S. participation in a war without any prompting (Alan, Alice, Jackie). Anouka proposed the United States apprehend, torture, and imprison members of the group in order to learn more about their organization; then, she committed the country to war.Only one reader, Malcolm—the oldest member of the sample—opposed a militarized foreign policy.

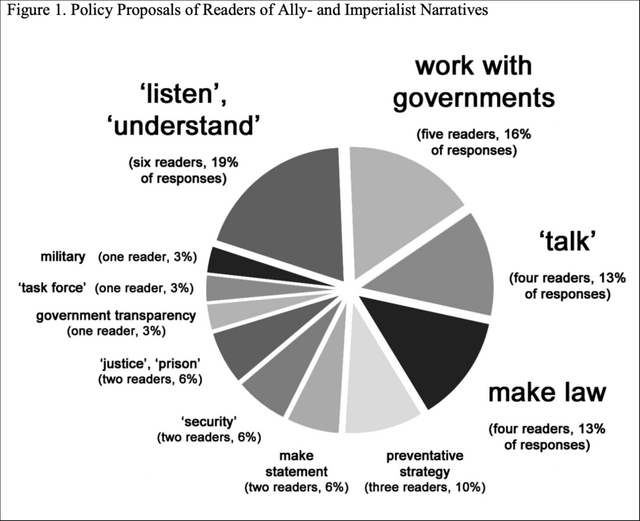

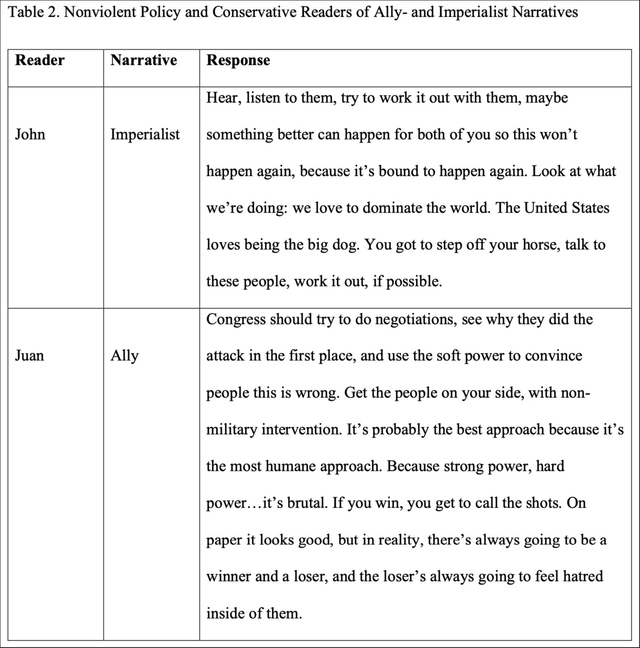

12 out of 13 did not believe the attack warranted a declaration of war or other militarized response. The most common foreign policy proposal, given by seven interviewees, consisted of using ‘talk’ to ‘understand’ the motivations of the attackers (five readers of the ally narrative: Juan, Landon, Magdaluz, May, Nicole; two, the imperialist narrative: John, Sofia). Five readers recommended working with another governmental body, such as another country or the United Nations (two readers of the imperialist narrative: Meghan, Srihan; three of the ally narrative: Landon, Magdaluz, Nicole). Four readers believed laws should be made (three readers of the imperialist narrative: Nyema, Sebastian, Srihan; one reader of the ally narrative: Nakolo). Of these, Sebastian suggested legislation to reduce income inequality abroad. Two readers of the imperialist narrative (Meghan, Nyema) proposed making a statement against the use of violence to achieve political aims. Only one reader, Srihan, advised ‘military action’ after considering five other steps Congress could take (but see his war views, next).

Of note, five out of eight readers identified their political orientation as conservative. Expressed conservative political orientation had little impact on their policy preferences:

Four out of seven stated war can solve problems (Alice, Anouka, Beth, Grace Morgan). Two were ambivalent (Alan and Jackie, despite having proposed a militarized policy). Beth was direct in her views about the efficacy of war. Consciously or unconsciously, she plagiarized a euphemism for destruction used on two occasions by the enemy narrative: ‘War can solve a lot of problems … It just brings a lot of death and destruction to a lot of cities, and it can make, just, completely, an entire country cease to exist’ (italics added to show convergence with the enemy narrative).

Despite his earlier endorsement of ‘military action’, Srihan distinguished himself as a ‘maybe’ regarding the efficacy of war, and recognized his hypocrisy:

I already contradicted what I just said…war is very avoidable. I mean, reading this article, it’s all based on the economy. But there are other ways. Resorting to war to solve problems is not good. It might solve problems. I’m not saying it will, but it might. Because the cause of terrorist groups has been the economy. I would say these terrorist groups form because a lot of governments don’t consider them. You can’t please anybody, but you should try your level best.

Srihan’s final word on the subject was consistent with the responses given by other readers of non-enemy narratives, of whom four stated that war did not solve problems (ally readers Juan and Magdaluz, imperialist readers Nyema and Srihan) or did not solve ‘most’ problems (Landon, reader of the ally narrative). The three exceptions (two readers of the imperialist narrative: John and Meghan; one reader of the ally narrative: Nakolo) each gave a weak ‘yes’ (but see the following section for greater insight). Five were ambivalent about the prospects of war (three readers of the imperialist narrative: Melody, Nicole, Sebastian; two of the ally narrative: May, Sofia). They emphasized the casualties that would result and often stated that the decision to declare war should depend on the situation—for example, to prevent a genocide.

Arguably John, a conservative, belongs in this category. While stating war can solve problems, his dejection with that course of action was palpable. To his own affirmation, he had been influenced by a history class he was taking at the time of our interview. A condensed excerpt is presented to illustrate John’s interest in the attackers’ intentions and his attempt to distinguish the 9/11 World Trade Center attack from the hypothetical attack on an unnamed ‘financial center’:

JOHN: Japan surrendered. Hitler lost. But, it’s horrible. I’ve realized, literally this semester, that a lot of history texts focus on the victory. I mean, you don’t want to teach that we bombed Japan and killed almost 200,000 people, hundreds of thousands innocent. Those were just citizens. That’s…insane. That is bloody…

INTERVIEWER: Do you think that war can solve problems?

JOHN: It depends on the severity of the attack. Like, obviously, in 9/11 we had to declare war. That was crazy. You can’t just do that. That was a blatant attack on us as a country. But if they attacked a financial center, it’s more for economic reasons. So, different motives…

By chance, many readers were exposed to narratives that challenged their political ideology. On two occasions, such interviews produced dramatic conversions. Meghan, a partisan conservative, held the imperialist narrative in low regard: she believed it showed bias in favor of Germany and imagined it had been written by a ‘liberal’. In spite of her disapproval, the text had a strong impact on her. Like other readers of ally- and imperialist narratives, she did not feel the attack justified war. Further, she accepted that no resolution may be possible if the attackers’ nation of origin did not collaborate with the United States. Asked if war can solve problems, she was torn. It was very important, and yet painfully difficult for her to distinguish between appropriate and inappropriate reasons to declare war. Eventually, she found support for war in the idea of ‘war rules’, such as the ‘Geneva Conventions’. However, she did not arrive at this conclusion without struggle, and appeared unconvinced by her own efforts.

Alice, a partisan liberal throughout the interview, also struggled to resist the narrative she had read—in her case, the enemy narrative. Faced with the hypothetical scenario, she immediately rejected the idea of the war, noting that wars cost money at the expense of public services like education. Earlier, she had even indicated that many of the ‘adjectives’ used by the narrative made her feel uncomfortable. Despite these positions, she persuaded herself to support war.

INTERVIEWER: What do you think the United States should do, in response to this situation?

ALICE: …Not go to war. That’s the answer to everything! Change it up! Don’t go to war. Because that is literally the answer for everything. In past times, if something happens, we go to war. That’s too much money. The military is a billion-dollar industry. That billion dollars can be used to fund other parts of the government, like education.

INTERVIEWER: Do you think that war can solve problems?

ALICE: …No. It hasn’t. It really hasn’t solved any problems, it just created a bigger—it kind of sort of did solve a problem, like in the case of this little article here, it did solve something…it solved the fact that we…had to…kill…a lot of people…to make sure…that…the people…hold on. Let me rephrase this. Like, it can, but it can’t. If we go to war for the wrong reasons…it’s not going to help…but if we go to war trying to better the future…then…Yes. It is a good thing to go to war…It has to be a legit reason…but…I don’t know what the reason should be. Maybe, because our stock market is our stock market…then that’s going to completely blow up the world. Because the world relies on our stock market. So…so, yes…it can, but it can’t, they should, but they shouldn’t…if it’s going to make sure that the economy becomes better again…if it’s for a good reason…if they blew up our stock market…I’d say, ‘Okay. Bye. Have fun, people…’

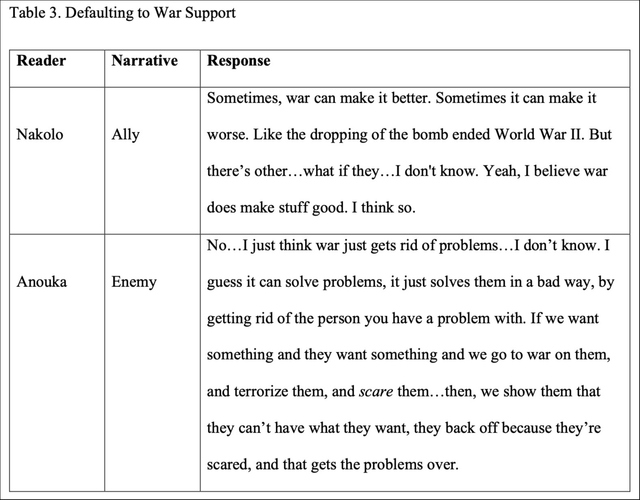

Asked whether war solves problems, a less dramatic pattern of conversion was also observed. I refer to the pattern as ‘defaulting’ because it consisted of an explicit, semiautomatic assumption that militarism is the dominant foreign policy of the United States, which can be endorsed in the absence of more persuasive ideas. On three occasions, readers first indicated opposition to war, or stated war can ‘make it worse’. The default occurred when readers attempted to qualify these positions, despite the fact I had not asked them to do so. Two readers of the enemy narrative (Alice and Anouka) defaulted, as did one reader of the ally narrative (Nakolo). In no case did a reader of the imperialist narrative default.

Emotion and cognition are inseparably linked. Although the bulk of Western scholarship has sought to break cognition into two, with ‘irrational’ emotion on one hand and ‘rational’, emotionless reason on the other, current scholarship shows that cognition is always motivated by emotion, even when we think we are behaving neutrally (Marcus, Neuman, and Makuen 2000). To a certain extent, emotions are rational: without them, we would be unable to interpret and respond to threats. Fear (and repeated experiences with fear) drive avoidance motivation, or avoidance behavior. Conversely, openness and hope follow from a prevailing experience of security and reflect the behavioral set of approach motivation.

The concept is easily applied to the findings presented here. In the enemy condition, participants experienced feelings of insecurity and the desire to eliminate its source via militarized foreign policy. In the ally- and imperialist conditions, participants experienced security and the desire to approach solutions fair to all. In light of what the participants had read, their responses can be considered intuitive. The real question, therefore, concerns how the respective narratives related to the patterns observed. A synthesis of prospect theory, social cognition, and the schemata literatures may hold the answer.

Prospect theory, as noted before, finds that risk assessments typically boil down to perceptions of loss/gain, as weighed from a reference point. According to the traditional theory, loss perception predicts risk-taking behaviors, whereas perception of gain predicts risk aversion. Prospect theory, however, has long lacked an account of the process whereby reference points are determined.

I must reiterate that in no case did a narrative prime not allude to the concept of loss as a result of war—whether loss of family, friends, career, good looks, ships, or planes. Yet, the experience of loss was not universally salient among the readers of the different narratives. To my initial surprise, in the prompt phase of the interviews, the emotional experience of loss was lowest among readers of the narratives that were the most explicit about suffering and death (the ally- and imperialist narratives). Meanwhile, for pro-war attitudes, the only narrative that mattered was the one that minimized death and silenced suffering. The same narrative maximized an enemy image that left no doubts about the hostile intentions of the enemy.

This pattern suggests that loss is experienced relative to the perceived intentions of the salient social actors and that reference points emerge from evaluations of those intentions. That is, an enemy narrative may condition an implicit loss response because one expects enemies to inflict loss. Said more directly: notions of loss and gain may be inherent to images.

If so, the implications go still further: through images, it may be possible to see how gains and losses are identified in realistic settings. In making this argument, I second Herrmann and colleagues (1997), the only authors of whom I’m aware to see the potential of image theory to generate a theory of the reference point:

[P]rospect theorists need to establish empirically how decision makers in the natural setting frame the circumstances as one of potential loss or gain, what they take to be the initial status quo, and what risks they assume are involved in not acting … We argue that these images provide the substantive definitions of situations in international relations that give meaning to more abstract concepts like benefits and costs and thus meet … [the] empirical challenge. (Herrmann et al. 1997, 404-405)

The emphasis on intentionality, or goals, is anticipated by social cognition research, including image theoretic work. Social cognition research finds that actors are preoccupied by perceptions of warmth (Wojciszke 2005) and care mightily about the perceived intentions of others (Fiske, Cuddy, and Glick 2007). Image theorists, meanwhile, maintain that group relations structure emotions, producing images associated with perceived intentions (Alexander, Brewer, and Herrmann 1999; Bilali 2010; Herrmann et al. 1997). Given the findings here, it seems likely that the process may also work in reverse, with images and perceived intentions structuring emotions and decisions in an unrelated domain, such as politics.

Ultimately, with prospect theory, a simpler and sharper conceptualization of images becomes possible. To repeat, prospect theory establishes that everyday decision-making boils down to perceptions of loss or gain. An enemy image should anticipate sensations of loss because the enemy’s presumed intention is to inflict harm, or loss. Conversely, it may be that multiple images relate to notions of gain. In the ally narrative, gains may have been inferred from the value- and goal-compatibility of the people described by the narrative. In the imperialist narrative, gains were corrupt: the ill begotten profits of elites who weighed economic power ahead of people. While negative, the narrative nevertheless highlighted the concept of gain for someone. Consistent with prospect theory, readers of the imperialist narrative avoided policies they associated with loss.

Some readers, including many readers of the enemy narrative, experienced fear in the prompt phase of the interview and assumed the scale of the attack had been significant. It is simple to grasp their reactions in terms of the psychological corpuses of both authoritarianism and cognition. Those who perceived threat favored punitive policies—the expected authoritarian response. Synthesizing the approaches, it is reasonable to assume threat perception is loss perception—specifically, the fear of future loss that follows from the perception of an enemy, as discussed before.

Authoritarianism research may also help to explain the complementary patterns observed. It has been found by Stenner (2005) that knowledge of others’ distress reduces authoritarian attitudes; Bizumic and colleagues (2013) find that it reduces support for war. In the present study, the ally narrative strongly emphasized the distress of people caught up in wars. In line with the aforementioned works, these readers were more pacifistic.

Attitudes consist of schemata pertaining to people, concepts, roles. Conceivably, therefore, schemata should help to explain default-style conversions and generalized war support, as well. In light of the relationship between prime frequency and schema strength—and assuming one has repeatedly experienced war discourse—it is exceedingly unlikely that a one-off encounter with an ally- or imperialist image would teach the schemata of peace. One-off encounters, by virtue of their infrequency, do not promote familiarity with new schemata. Assuming the individual does not immediately go with the ingrained, culturally prevalent schema, it is comprehensible why a ‘default’ to a hegemonic position might follow initial efforts to contradict that position. The hegemonic schema—liked or disliked—forms part of an implicit attitude.

In effect, schemata may help to explain why explicit and implicit attitudes on a given topic can differ (Ksiazkicwics and Hedrick 2013). Alice, for example, was very progressive on an explicit, or conscious level. On an implicit level, she appears to have been much less so. Indeed, Alice’s initial position against war demonstrated her familiarity with war schemata. Accordingly, upon failing to make sense of her explicit attitude, she apparently defaulted to an implicit one. The pattern suggests that the frequency of schema exposure structures implicit attitudes.

Nevertheless, ally- and imperialist narratives may still help to provide familiarity and, over the longer term, empower individuals to overcome culturally conditioned war schemata. The case of John, a conservative student who mentioned being influenced by a class he was taking, speaks to the importance of familiarity for the development of peace schemata. By chance, a more expressly conservative student, Meghan, read the same text. Although she did not like the narrative, she could not reject its implicit message. Instead, she adapted it, along with her preexisting viewpoints. Said another way, Meghan exhibited constraint as a result of exposure to competing information—a key indicator of attitude change.

The act of reading involves implicit cognitive processes, such as emotion, which are social in nature, largely unconscious, and which aim for the survival of an organism. Because both the acts of reading and navigating social environments involve implicit processes, emotional experiences as a result of reading may carry over to shape responses to real-life events. We can begin to comprehend how reading—and experiences with narratives in general, regardless of medium—relate to perceptions in an unrelated domain by investigating the ‘images’ imbued by narrative accounts.

To explore such a relationship in the context of history education and war attitudes, the present research exposed participants to ‘narrative primes’ structured around distinct ‘images’. Subsequently, three areas were examined in depth: emotional responses and policy preferences relative to a hypothetical attack, as well as generalized attitudes about war. The resultant data was strongly supportive of a relationship between narratives and each area of focus. Indeed, exposure to narratives—more than any other variable measured, including political affiliation—emerged as the most significant predictor of feelings, preferences, and attitudes.

In combination with the hypothetical attack, exposure to an enemy narrative related to an exaggerated sense of loss, fear, and inattention to the attackers’ stated intentions, as well as difficulty imagining alternatives to conflict. Readers of ally- and imperialist narratives had another experience. Although many readers did not seem to recall the attackers’ motives, they expressed interest in discovering them. Furthermore, they believed that talk, mediation, laws, and nonviolent policy could resolve the differences that had precipitated the attack. Some participants had the opportunity to read narratives that contradicted their political views. Their responses underscored the power of images to overcome political conditioning.

The findings were considered in light of multiple literatures. Microcognitive schemata literatures lent themselves to many of the phenomena observed, from the relationship between primes, emotions, policies, and attitudes, to the ‘conversions’ and ‘defaults’. Other phenomena were more complex. Initially, prospect theory—a well-known theory of decision-making that has routinely demonstrated the relationship between loss perception and risk-taking—did not appear to fit the data. The ally- and imperialist narratives were both explicit about wartime losses, and yet, neither text elicited the emotional experience of loss. Nor did they relate to unambiguously risky behavior. Instead, the enemy narrative related to unambiguously risky policy preferences: most especially, a preference for foreign military campaigns that would assuredly cost lives in exchange for uncertain gains.

An even deeper reading of the image theory literature suggested why this might be. By definition, enemy images convey hostile intentions, and in the present experiment, it was precisely the readers of the enemy narrative who attributed hostility to the unnamed, hypothetical attackers in the prompt phase of the research interviews. Conversely, individuals who had read ally- and imperialist narratives were disinclined to infer hostile motives on the part of the attackers. To explain this pattern, it was proposed that notions of loss and gain are probably inherent to images.

The implications go beyond the present study: if notions of loss/gain are inherent to images, image theory should help to complete prospect theory. Current prospect theory cannot explain how individuals define losses and gains as such. It cannot because it lacks a theory of the ‘reference point’ against which the options for action are framed. However, I argue, narrative imagery may function as the ‘reference point’ where decision-making involves social actors. Since narrative imagery is not limited to reading, the principle should have application anytime communication takes place.

Finally, the paper sought to explore its findings in light of authoritarianism research. In so doing, the present study provided insight into the oppositional attitude long taken for granted within authoritarianism research. Previously, this attitude has been referred to as ‘non-’, ‘anti-’, and even ‘low-’ authoritarianism, as well as ‘libertarian’ and ‘democratic’. Rarely has consideration been given to the concept of empathy, and studies have often lacked data. Here, evidence was generated that the counterpart of the authoritarian attitude may be an implicit empathetic attitude that feels problems are best resolved by availing oneself of different viewpoints, instead of punishing them. This conclusion was reached by comparing patterns of response to different narratives, instead of directly testing the authoritarian hypothesis.

Further research with larger samples will be necessary to clarify these findings and initial conclusions. The effort, however, seems well worth it. In the present study, when students primed to think in terms of people and profit were faced with crisis, they did not view violence as inevitable. Instead, they sought alternatives to violence. Moreover, by seeking to include others in the resolution of the conflict, they became true democrats. Images, it appears, define the boundaries of what seems rational and feasible in a given decision-making context. By emphasizing ‘allies’ and ‘imperialists’ over ‘enemies’, policymakers and educators may be able to expand students’ emotional and political horizons. If this is the case, past may be prologue, but it is we who write the past. It is time to write the past humanely.

Adorno, Theodor W., Else Frenkel-Brunswik, Daniel Levinson, and Nevitt Sanford. 1950. The Authoritarian Personality. New York: Harper and Row.

Alexander, Michele G., Marilynn B. Brewer, and Richard K. Herrmann. 1999. “Images and affect: A functional analysis of out-group stereotypes.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77, (1): 78-93. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.1.78

Aronson, Elliot. 2011. The Social Animal. New York: Worth Publishers.

Asch, S. E. 1946. “Forming impressions of personality.” The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 41 (3): 258-290. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0055756

Åström Elmerslö, Henrik, and Daniel Lindmark. 2010. “Nationalism, peace education, and history textbook revision in Scandinavia, 1886-1940.” Journal of Educational Media, Memory and Society 2 (2): 63-74. https://doi.org/10.3167/jemms.2010.020205

Bar-Tal, Daniel. 2001. “Why does fear override hope in societies engulfed by intractable conflict, as it does in the Israeli society?” Political Psychology 22 (3): 601-627. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00255

Bilali, Rezarta. 2010. “Assessing the internal validity of image theory in the context of Turkey-U.S. relations.” Political Psychology 31 (2): 275-303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2009.00752.x

Bizumic, Boris, Rune Stubager, Scott Mellon, Nicolas Van der Linden, Ravi Iyer, and Benjamin M. Jones. 2013. “On the (in)compatibility of attitudes toward peace and war.” Political Psychology 34 (5): 673-693. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12032

Boulding, Kenneth E. 1956. The Image: Knowledge in Life and Society. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Boulding, Kenneth E. 1959. “National images and international systems.” The Journal of Conflict Resolution 3 (2): 120-131. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F002200275900300204

D’Andrade, Roy, and Claudia Strauss. 1992. Human Motives and Cultural Models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

D’Andrade, Roy. 1995. The Development of Cognitive Anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Danzer, Gerald A., J. J. Klor de Alva, L. S. Krieger, Louis E. Wilson, and Nancy Woloch. 2006. The Americans: Reconstruction to the 21st Century. Boston, MA: McDougal Littell.

Doty, Richard M., Bill E. Peterson, and David G. Winter. 1991. “Threat and authoritarianism in the United States, 1978-1987.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 61 (4): 629-640. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.4.629

Duckitt, John. 1989. “Authoritarianism and group identification: A new view of an old construct.” Political Psychology 10 (1): 63-84. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.2307/3791588

Dunn, Kris. 2013. “Preference for radical right-wing populist parties among exclusive-nationalists and authoritarians.” Party Politics 21 (3): 367-380. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1354068812472587

Dweck, Carol S. 2008. “Can personality be changed? The role of beliefs in personality and change.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 17 (6): 391-394. https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1467-8721.2008.00612.x

Eicher, Véronique, Felicia Pratto, and Peter Wilhelm. 2013. “Value differentiation between enemies and allies: Value projection in national images.” Political Psychology 34 (1): 127-144. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2012.00930.x

Elliot, Andrew J., and Martin V. Covington. 2001. “Approach and avoidance motivation.” Educational Psychological Review 13 (2): 73-92. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009009018235

Feldman, Stanley, and Karen Stenner. 1997. “Perceived threat and authoritarianism.” Political Psychology 18 (4): 741-770. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00077

Ferguson, Melissa J., and Vivian Zayas. 2009. “Automatic evaluation. Current Directions in Psychological Science” 18 (6): 362-366. https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1467-8721.2009.01668.x

Fiske, Susan T., Amy J. Cuddy, and Peter Glick. 2007. “Universal dimensions of social cognition: warmth and competence.” TRENDS in Cognitive Sciences 11 (2): 77-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005

Fromm, Erich. 1941. Escape from Freedom. New York: Farrar and Rinehart.

Gayer, Corinna C., Shiri Landman, Eran Halperin, and Daniel Bar-Tal. 2001. “Overcoming psychological barriers to peaceful conflict resolution: The role of arguments about losses.” The Journal of Conflict Resolution 53 (6): 951-975. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022002709346257

Greenstein, Fred I. 1965. “Personality and political socialization: The theories of authoritarianism and democratic character.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 361 (1): 81-95. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F000271626536100108

Henry, P. J. 2011. “The role of stigma in understanding ethnicity differences in authoritarianism.” Political Psychology 32 (3): 419-438. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00816.x

Herrmann, Richard K., James F. Voss, Tonya Y. E. Schooler, and Joseph Ciarrochi. 1997. “Images in international relations: An experimental test of cognitive schemata.” International Studies Quarterly 41 (3): 403-433. https://doi.org/10.1111/0020-8833.00050

Hetherington, Marc J., and Elizabeth Suhay. 2011. “Authoritarianism, threat, and Americans’ support for the war on terror.” American Journal of Political Science 55 (3): 546-560. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00514.x

Hetherington, Marc J., and Jonathan D. Weiler. 2009. Authoritarianism and Polarization in American Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kahneman, Daniel. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Ksiazkiewicz, Aleksander, and James Hedrick. 2013. “An introduction to implicit attitudes in political science research.” PS: Political Science and Politics 46 (3): 525-531. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096513000632

Lasswell, Harold D. 1951. The Political Writings of Harold D. Lasswell. New York: The Free Press.

Lavine, Howard, Milton Lodge, and Kate Freitas. 2005. “Threat, authoritarianism, and selective exposure to information.” Political Psychology 26 (2): 219-244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00416.x

Levy, Jack S. 1997. “Prospect theory, rational choice, and international relations.” International Studies Quarterly 41 (1): 87-112. https://doi.org/10.1111/0020-8833.00034

Levy, Jack S. 2003. “Applications of prospect theory to political science.” Synthese 135 (2): 215-241. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023413007698

Luostarinen, Heikki. 1989. “Finnish Russophobia: The story of an enemy image.” Journal of Peace Research 26 (2): 123-137. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022343389026002002

Marcus, George E., W. R. Neuman, and Michael Makuen. 2000. Affective Intelligence and Political Judgment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Marsden, W. E. 2000a. “Geography and two centuries of education for peace and international understanding.” Geography 85 (4): 289-302. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40573474

Marsden, William E. 2000b. “‘Poisoned history’: A comparative study of nationalism, propaganda, and the treatment of war and peace in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth century-school curriculum.” History of Education 29 (1): 29-47. https://doi.org/10.1080/004676000284472

Martin, John L. 2001. “‘The Authoritarian Personality,’ 50 years later: What lessons are there for political psychology?” Political Psychology 22 (1): 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00223

Melby, Ernest O. 2006. “Authoritarianism: Enslaving yoke of nations and schools.” The Clearing House 79 (5): 224-227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.1938.11475126

Murray, Kathleen S., and Jonathan A. Cowden. 1999. “The role of ‘enemy images’ and ideology in elite belief systems.” International Studies Quarterly 43 (3): 455-481. https://doi.org/10.1111/0020-8833.00130

Oesterreich, Detlef. 2005. “Flight into security: A new approach and measure of the authoritarian personality.” Political Psychology 26, (2): 275-297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00418.x

Oppenheimer, Louis. 2005. “The development of enemy images in Dutch children: Measurement and initial findings.” British Journal of Developmental Psychology 23 (4): 645-660. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151005X36155

Perla, Héctor. 2011. “Explaining public support for the use of military force: The impact of reference point framing and prospective decision making.” International Organization 65 (1): 139-167. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818310000330

Perrin, Andrew J. 2005. “National threat and political culture: Authoritarianism, antiauthoritarianism, and the September 11 attacks.” Political Psychology 26 (2): 167-194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00414.x

Rice, Elizabeth. 1980. “On cultural schemata.” American Ethnologist 7 (1): 152-171. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.1980.7.1.02a00090

Rigberg, Benjamin. 1991. “What must not be taught.” Theory and Research in Social Education 19 (1): 14-44. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.1991.10505626

Rumelhart, David E., James L. McClelland, and PDP Research Group. 1986. Parallel Distributed Processing: Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Scott, Seth B. “The perpetuation of war in U.S. history textbooks.” Journal of Educational Media, Memory & Society 1 (1): 59-70. https://doi.org/10.3167/jemms.2009.010105

Siegel, Mona, and Kirsten Harjes. 2012. “Disarming hatred: History education, national memories, and Franco-German reconciliation from World War I to the Cold War.” History of Education Quarterly 52 (3): 370-402. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5959.2012.00404.x

Smith, Eliot R. 1996. “What do connectionism and social psychology offer each other?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70 (5): 893-912. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.70.5.893

Spellman, Barbara A., Jodie B. Ullman, and Keith J. Holyoak. 1993. “A coherence model of cognitive consistency: Dynamics of attitude change during the Persian Gulf War.” Journal of Social Issues 49 (4): 147-165. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1993.tb01185.x

Stellmacher, Jost, and Thomas Petzel. 2005. “Authoritarianism as a group phenomenon.” Political Psychology 26 (2): 245-274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00417.x

Stenner, Karen. 2005. The Authoritarian Dynamic. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Terkel, Studs. 1985. The ‘Good War’. New York: Ballantine.

Tversky, Amos, and Daniel Kahneman. 1981. “The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice.” American Association for the Advancement of Science 211 (4481): 453-458. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.7455683

Wojciszke, Bogdan. 2005. “Morality and competence in person- and self-perception.” European Review of Social Psychology 16 (1): 155-188. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463280500229619

Zinn, Howard. 2010. A People’s History of the United States. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

Adorno, Theodor W., Else Frenkel-Brunswik, Daniel Levinson, and Nevitt Sanford. 1950. The Authoritarian Personality. New York: Harper and Row.

Alexander, Michele G., Marilynn B. Brewer, and Richard K. Herrmann. 1999. “Images and affect: A functional analysis of out-group stereotypes.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77, (1): 78-93. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.1.78

Aronson, Elliot. 2011. The Social Animal. New York: Worth Publishers.

Asch, S. E. 1946. “Forming impressions of personality.” The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 41 (3): 258-290. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0055756

Åström Elmerslö, Henrik, and Daniel Lindmark. 2010. “Nationalism, peace education, and history textbook revision in Scandinavia, 1886-1940.” Journal of Educational Media, Memory and Society 2 (2): 63-74. https://doi.org/10.3167/jemms.2010.020205

Bar-Tal, Daniel. 2001. “Why does fear override hope in societies engulfed by intractable conflict, as it does in the Israeli society?” Political Psychology 22 (3): 601-627. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00255

Bilali, Rezarta. 2010. “Assessing the internal validity of image theory in the context of Turkey-U.S. relations.” Political Psychology 31 (2): 275-303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2009.00752.x

Bizumic, Boris, Rune Stubager, Scott Mellon, Nicolas Van der Linden, Ravi Iyer, and Benjamin M. Jones. 2013. “On the (in)compatibility of attitudes toward peace and war.” Political Psychology 34 (5): 673-693. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12032

Boulding, Kenneth E. 1956. The Image: Knowledge in Life and Society. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Boulding, Kenneth E. 1959. “National images and international systems.” The Journal of Conflict Resolution 3 (2): 120-131. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F002200275900300204

D’Andrade, Roy, and Claudia Strauss. 1992. Human Motives and Cultural Models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

D’Andrade, Roy. 1995. The Development of Cognitive Anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Danzer, Gerald A., J. J. Klor de Alva, L. S. Krieger, Louis E. Wilson, and Nancy Woloch. 2006. The Americans: Reconstruction to the 21st Century. Boston, MA: McDougal Littell.

Doty, Richard M., Bill E. Peterson, and David G. Winter. 1991. “Threat and authoritarianism in the United States, 1978-1987.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 61 (4): 629-640. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.4.629

Duckitt, John. 1989. “Authoritarianism and group identification: A new view of an old construct.” Political Psychology 10 (1): 63-84. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.2307/3791588

Dunn, Kris. 2013. “Preference for radical right-wing populist parties among exclusive-nationalists and authoritarians.” Party Politics 21 (3): 367-380. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1354068812472587

Dweck, Carol S. 2008. “Can personality be changed? The role of beliefs in personality and change.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 17 (6): 391-394. https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1467-8721.2008.00612.x

Eicher, Véronique, Felicia Pratto, and Peter Wilhelm. 2013. “Value differentiation between enemies and allies: Value projection in national images.” Political Psychology 34 (1): 127-144. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2012.00930.x

Elliot, Andrew J., and Martin V. Covington. 2001. “Approach and avoidance motivation.” Educational Psychological Review 13 (2): 73-92. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009009018235

Feldman, Stanley, and Karen Stenner. 1997. “Perceived threat and authoritarianism.” Political Psychology 18 (4): 741-770. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00077

Ferguson, Melissa J., and Vivian Zayas. 2009. “Automatic evaluation. Current Directions in Psychological Science” 18 (6): 362-366. https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1467-8721.2009.01668.x

Fiske, Susan T., Amy J. Cuddy, and Peter Glick. 2007. “Universal dimensions of social cognition: warmth and competence.” TRENDS in Cognitive Sciences 11 (2): 77-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005

Fromm, Erich. 1941. Escape from Freedom. New York: Farrar and Rinehart.

Gayer, Corinna C., Shiri Landman, Eran Halperin, and Daniel Bar-Tal. 2001. “Overcoming psychological barriers to peaceful conflict resolution: The role of arguments about losses.” The Journal of Conflict Resolution 53 (6): 951-975. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022002709346257

Greenstein, Fred I. 1965. “Personality and political socialization: The theories of authoritarianism and democratic character.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 361 (1): 81-95. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F000271626536100108

Henry, P. J. 2011. “The role of stigma in understanding ethnicity differences in authoritarianism.” Political Psychology 32 (3): 419-438. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00816.x

Herrmann, Richard K., James F. Voss, Tonya Y. E. Schooler, and Joseph Ciarrochi. 1997. “Images in international relations: An experimental test of cognitive schemata.” International Studies Quarterly 41 (3): 403-433. https://doi.org/10.1111/0020-8833.00050

Hetherington, Marc J., and Elizabeth Suhay. 2011. “Authoritarianism, threat, and Americans’ support for the war on terror.” American Journal of Political Science 55 (3): 546-560. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00514.x

Hetherington, Marc J., and Jonathan D. Weiler. 2009. Authoritarianism and Polarization in American Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kahneman, Daniel. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Ksiazkiewicz, Aleksander, and James Hedrick. 2013. “An introduction to implicit attitudes in political science research.” PS: Political Science and Politics 46 (3): 525-531. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096513000632

Lasswell, Harold D. 1951. The Political Writings of Harold D. Lasswell. New York: The Free Press.

Lavine, Howard, Milton Lodge, and Kate Freitas. 2005. “Threat, authoritarianism, and selective exposure to information.” Political Psychology 26 (2): 219-244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00416.x

Levy, Jack S. 1997. “Prospect theory, rational choice, and international relations.” International Studies Quarterly 41 (1): 87-112. https://doi.org/10.1111/0020-8833.00034

Levy, Jack S. 2003. “Applications of prospect theory to political science.” Synthese 135 (2): 215-241. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023413007698

Luostarinen, Heikki. 1989. “Finnish Russophobia: The story of an enemy image.” Journal of Peace Research 26 (2): 123-137. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022343389026002002

Marcus, George E., W. R. Neuman, and Michael Makuen. 2000. Affective Intelligence and Political Judgment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Marsden, W. E. 2000a. “Geography and two centuries of education for peace and international understanding.” Geography 85 (4): 289-302. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40573474

Marsden, William E. 2000b. “‘Poisoned history’: A comparative study of nationalism, propaganda, and the treatment of war and peace in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth century-school curriculum.” History of Education 29 (1): 29-47. https://doi.org/10.1080/004676000284472

Martin, John L. 2001. “‘The Authoritarian Personality,’ 50 years later: What lessons are there for political psychology?” Political Psychology 22 (1): 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00223

Melby, Ernest O. 2006. “Authoritarianism: Enslaving yoke of nations and schools.” The Clearing House 79 (5): 224-227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.1938.11475126

Murray, Kathleen S., and Jonathan A. Cowden. 1999. “The role of ‘enemy images’ and ideology in elite belief systems.” International Studies Quarterly 43 (3): 455-481. https://doi.org/10.1111/0020-8833.00130

Oesterreich, Detlef. 2005. “Flight into security: A new approach and measure of the authoritarian personality.” Political Psychology 26, (2): 275-297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00418.x

Oppenheimer, Louis. 2005. “The development of enemy images in Dutch children: Measurement and initial findings.” British Journal of Developmental Psychology 23 (4): 645-660. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151005X36155

Perla, Héctor. 2011. “Explaining public support for the use of military force: The impact of reference point framing and prospective decision making.” International Organization 65 (1): 139-167. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818310000330

Perrin, Andrew J. 2005. “National threat and political culture: Authoritarianism, antiauthoritarianism, and the September 11 attacks.” Political Psychology 26 (2): 167-194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00414.x

Rice, Elizabeth. 1980. “On cultural schemata.” American Ethnologist 7 (1): 152-171. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.1980.7.1.02a00090

Rigberg, Benjamin. 1991. “What must not be taught.” Theory and Research in Social Education 19 (1): 14-44. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.1991.10505626

Rumelhart, David E., James L. McClelland, and PDP Research Group. 1986. Parallel Distributed Processing: Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Scott, Seth B. “The perpetuation of war in U.S. history textbooks.” Journal of Educational Media, Memory & Society 1 (1): 59-70. https://doi.org/10.3167/jemms.2009.010105

Siegel, Mona, and Kirsten Harjes. 2012. “Disarming hatred: History education, national memories, and Franco-German reconciliation from World War I to the Cold War.” History of Education Quarterly 52 (3): 370-402. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5959.2012.00404.x

Smith, Eliot R. 1996. “What do connectionism and social psychology offer each other?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70 (5): 893-912. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.70.5.893

Spellman, Barbara A., Jodie B. Ullman, and Keith J. Holyoak. 1993. “A coherence model of cognitive consistency: Dynamics of attitude change during the Persian Gulf War.” Journal of Social Issues 49 (4): 147-165. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1993.tb01185.x

Stellmacher, Jost, and Thomas Petzel. 2005. “Authoritarianism as a group phenomenon.” Political Psychology 26 (2): 245-274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00417.x

Stenner, Karen. 2005. The Authoritarian Dynamic. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Terkel, Studs. 1985. The ‘Good War’. New York: Ballantine.

Tversky, Amos, and Daniel Kahneman. 1981. “The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice.” American Association for the Advancement of Science 211 (4481): 453-458. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.7455683

Wojciszke, Bogdan. 2005. “Morality and competence in person- and self-perception.” European Review of Social Psychology 16 (1): 155-188. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463280500229619

Zinn, Howard. 2010. A People’s History of the United States. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

[ad_2]

Source link