Forensic Psychology, Criminology, or Criminal Psych: A Guide

[ad_1]

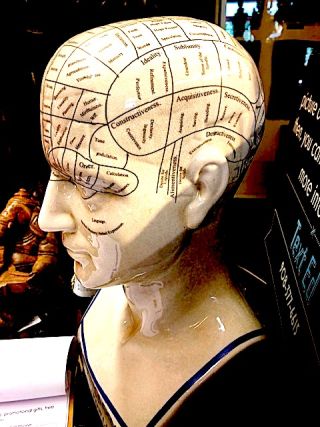

Photo by K. Ramsland

I’m a professor. I teach forensic psychology, consult on ambiguous deaths, and specialize in serial killers. In the news recently, I’ve been described as a forensic psychologist, a criminologist, a criminal psychologist, a criminalist, and a profiler. Some journalists seem to think these disciplines are interchangeable—an error that could confuse those who hope to pursue one of these careers. There’s certainly overlap in subject areas, but we should be clear when we guide students toward one of these fields.

Here’s a basic overview:

Forensic psychologist. This discipline covers those interactions between law enforcement and psychology that benefit from psychological research and clinical experience. Such practitioners can apply their knowledge and experience in both the civil and criminal arenas. I have previously written a post about forensic psychology’s different areas, so I’ll keep it simple here. Many forensic psychologists are licensed clinicians in private therapeutic practice who work in the legal arena. For the court, they might perform assessments to evaluate defendants’ present or past mental states, psychological disorders, or future potential for violence. They might use their expertise to help triers-of-fact make informed decisions about specialized areas.

Some of these professionals work for police departments to screen for fitness for duty, teach stress management, or determine the need for trauma counseling. Many work in prisons. Some focus on research or teaching. They provide insight about such behaviors as deception, eyewitness memory, risk evaluation, jury dynamics, false confessions, and the criminal mind.

Criminologist. This discipline studies crime and criminal behavior, usually from a sociological perspective, specifically regarding trends and causal factors; they devise ways to contain or prevent it. No clinical license is required.

The description for a criminology course at the renowned John Jay College of Criminal Justice reads like this: “Criminology is the study of crimes, criminals, crime victims, theories explaining illegal and deviant behavior, the social reaction to crime and criminals, the effectiveness of anti-crime policies, and the broader political terrain of social control.”

Many criminologists are academics, but some also apply their education and training in a hands-on investigative environment. That is, they might include criminalistics, or the science of analyzing physical evidence from a crime. This combination is often referred to as forensic criminology, with an emphasis on forensic science. A criminologist and a criminalist are different types of professionals, but the data and methods from each area complement the other.

Forensic criminologist Laura Pettler blends criminology and criminalistics in her private death investigation practice and her trainings for law enforcement and medicolegal personnel. “As a forensic criminologist, I source data from forensic science, sociology, psychology, and law to analyze, explain, and predict offender behavior in criminal acts,” Pettler says. “I’m also an expert in bloodstain pattern analysis, bullet trajectory reconstruction, and staged homicide scenes. These areas work together for accurate scene reconstruction.”

Criminal Psychologist. This professional (a label used more often in other countries than in the U.S.) shares much in common with both criminologists and forensic psychologists, but there are differences. Forensic psychologists tend to work in the aftermath of crime, evaluating mental state, analyzing data, and counseling victims (or offenders), while criminal psychologists focus on motive, criminal experience, and the prediction of offenders’ future behavior. They often work in police departments and might have a law enforcement background. Criminology and data analytics serve them well, but they rely more on psychological theory covering abnormal psychology, personality, and individual cognition relevant to crime. To become a clinical criminal psychologist requires licensing and a period of supervision.

Profiler. Profiling is an activity, not really a job description. For the FBI, devising a profile is just one part of Criminal Investigative Analysis (CIA). Former FBI Supervisory Special Agent Gregg McCrary, once a member of the Behavioral Analysis Unit, explains: “Criminal Investigative Analysis is a multi-stage process for analyzing a crime or a series of crimes. Under certain circumstances, CIA can produce a product – a profile – that will help to focus the investigation. Profiling may or may not occur during the course of CIA, but it can be a helpful tool to narrow the list of suspects. To produce a profile, we integrate details from the broader analysis of the crimes with relevant forensic data from police and autopsy reports to infer a list of offender characteristics and traits. The purpose of profiling is to offer productive investigative, interview, and trial strategies.”

I haven’t covered all the nuances, but with students in mind, I hope I’ve abated some of the confusion. In each of these professions, there are many ways to create a unique and satisfying career.

[ad_2]

Source link