Judy Baca, the renowned Chicana muralist who paints LA’s forgotten history: ‘My art is meant to heal’ | Art

[ad_1]

Judy Baca still recalls the day in the 1970s when the curator of an exhibit showcasing the work of emerging Los Angeles artists told her she couldn’t possibly include Baca in the show. “These are only people touched by an angel,” Baca remembers the woman saying about the the all-male group of artists she had selected. The message was clear: Baca was not worthy of a museum.

Fifty years later, Baca’s an internationally celebrated artist, whose large-scale works of public art have left an unmatched imprint on the artistic landscape of LA. And the Chicana muralist, scholar and activist is now receiving long overdue mainstream recognition. The Museum of Latin American Art (Molaa) in Long Beach, California, is running the first major retrospective on her work, and a major show at the Museum of Contemporary Art (Moca) in Los Angeles is planned for September.

“I never expected to be part of the 1% that would live on my art,” Baca, 75, said in a recent interview. “This is the first time in my career in which people are seeking to buy my work, to own pieces of the Judy Baca collection.”

For years, Baca said, the white, male-dominated art industry was uninterested in her. “My work has been ignored a lot in LA … and the men here have been pretty profoundly unable to see women as their peers. That’s been the struggle of my whole life as a Chicana and activist and feminist. It’s created a devil-may-care attitude for me. I had to just perceive what I was doing as significant for myself and my community and move ahead with willfulness and belief, buoyed by the community people I worked with – not by the arts.”

Baca was born in Watts, an LA neighborhood known for the 1965 uprisings, and grew up in Pacoima, near the LA river. Her grandparents came from Mexico to La Junta, Colorado during the Mexican Revolution, a story told in her Denver airport mural, La Memoria de Nuestra Tierra, and at the entrance of her Molaa retrospective.

“This was the first massive migration of Mexican people into the United States … although in some ways, we didn’t cross the border, the border crossed us,” she said.

While her mother worked at a factory in her early childhood, her grandmother raised her and had a huge influence on her creativity: “My grandmother had a special relationship with the spirit world. She would begin my day by saying, ‘What did you dream?’ … I realized there was more to living than simply what was visible, tangibly.”

Her grandma’s indigenous identity also shaped her: “People were not able to own their indigeneity, because it was not considered attractive or good. But my grandmother was indigenous and she looked Apache.” Baca’s grandmother practiced a kind of “curanderismo”, meaning people came to her for counsel and healing.

Baca’s mother worried she would not earn a living as an artist and encouraged her to get a degree in education – a path that led her to muralism.

Baca created her first mural while working at a Catholic high school, as a way to channel the students’ interest in graffiti. (She was later fired from the school after marching against the Vietnam war.)

In 1974, she launched the city of LA’s first mural program, which produced over 400 murals and soon after, co-founded the Social and Public Art Resource Center (Sparc), a public art community organization, housed in an old jailhouse.

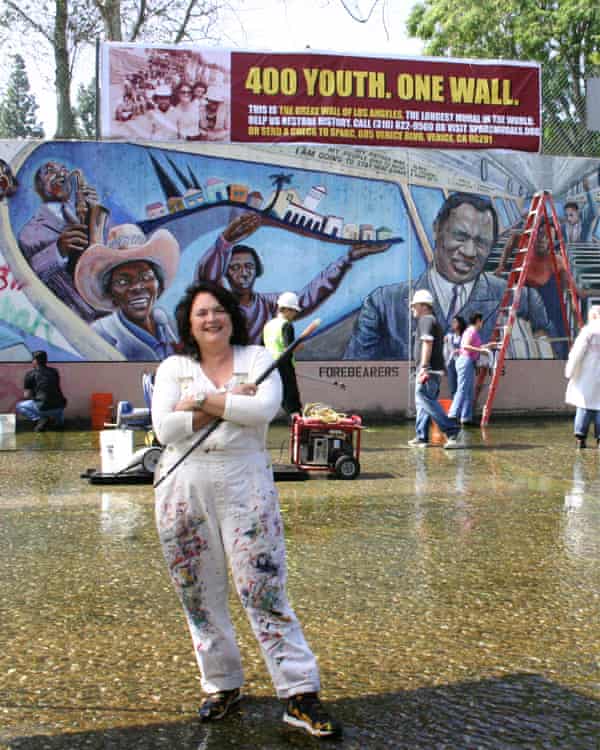

Baca began building the Great Wall of Los Angeles, in 1976 along the Tujunga wash in the San Fernando Valley, with the idea of painting a “tattoo on the scar where the river once ran”. Originally named The History of California, the mural is one of the longest in the world and depicts forgotten histories of people of color in California.

Over five years, she worked with hundreds of youth – some of whom were diverted from the criminal justice system – to paint a visual history of stories that disappeared along with the river, from prehistoric times to the 1950s.

The narratives within the 2,754-ft mural include a little-known massacre of Chinese people in LA in 1871; the mass deportations of Mexican Americans in the 1930s; and a portrait of Luisa Moreno, a farm-workers labor organizer in the 1940s.

“What I learned from the young people who participated is that it changed forever the way that they saw each other,” Baca said. “We were in segregated communities … but they were all sort of ‘rejects’, thought to be young people who will never succeed. But that mixing with each other, which has continued for a lifetime, was a remarkable change.”

In 1980, Baca became a professor in studio art at the University of California, the only Chicana to have a tenured position in visual arts and one of a handful of senior Chicana professors across the public university system.

The Molaa exhibit includes more than 110 of Baca’s works, spotlighting the history of the Great Wall, and featuring paintings, sculptures and early drawings. There are portraits of her dressed as a “pachuca” in the 1970s for LA’s first all-Chicana show; her striking Josefina: Ofrenda to the Domestic Worker print; a vendor cart painted with histories of the criminalization of undocumented people; and study drawings of the World Wall, her mural that has traveled around the globe.

Gabriela Urtiaga, Molaa’s chief curator, said in an email that Baca “has always [been] and continues to be a pivotal figure looking for new alternatives to speak about silenced voices, and the figure of women as an essential part of her creative work”, adding, “Judy rethinks a collective memory and identity as a fundamental link in the construction of women’s power – Chicana, Latina, women of color.”

Some of the most fascinating displays capture obstacles she overcame. On a draft drawing of a mural commissioned for the University of Southern California in the 1990s, she wrote down critiques from administrators who tried to censor the painting, which depicted conflicts, violence and resistance movements involving Latinos in LA: “Judy, we believe that this mural is not understandable to an Anglo audience and is too negative. The history you represent is depressing.”

“I do not make the history, I just paint about it,” she responded on the mural draft.

The exhibit also chronicles the reaction to Danzas Indigenas, a monument she created in 1994 at an LA rail station, meant to honor indigenous history in the region. In 2005, an anti-immigrant group, Save Our State, protested the monument; the footage on display closely resembles the white supremacist rallies of recent years and the growing push to erase teachings of racism in America.

“I hope the show reminds people that we’re dealing with the same thing over and over again, and if we don’t fix it, we have to keep reliving it,” Baca said, adding that seeing decades of her work curated in a museum format has been validating.

“I always thought I’d make a work and it’d go out into the ether, never to be seen again or spoken about,” she said. “But I realized that when I was making it, that I was processing through my hands, and through my art. I was finding a way to live with truth that was hard and difficult. It was a way of keeping me sane, and keeping me in the process of healing, and healing those around me … and I’ve learned that my instincts were good.”

Why does she believe she is finally getting proper recognition?

“Maybe they think I’m gonna die,” she said with a laugh, adding that the recent social justice uprisings have forced a reckoning in the arts. For so long, she said, “It was the gatekeepers, and the remarkable failure to deal with the Latino community in any real way. I think it’s a lot about the referencing and metaphors that define a people as ‘aliens’.”

Last year, the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art acquired the archives related to the Great Wall, and the Andrew W Mellon Foundation awarded Sparc $5m to expand the wall to include stories from the 1960s to 2020. The 1960s section will feature a “generation on fire” fighting Jim Crow and Alabama firemen hosing protesters. The 70s will start with the Alcatraz occupation, with a quote from Oglala Lakota leader Red Cloud: “They made us many promises … but they kept but one; they promised to take our land, and they did.”

While Baca is hopeful about her future projects, she is disheartened about the state of the art form: “Muralism as a whole has been diminished in LA. It’s totally commercial. The only things that can get made are those paid by corporations that want to decorate buildings.”

She lamented that the city lacked the kind of public program that she launched in the 70s, noting how murals can shape our understanding of history and “create sites of public memory” when done with communities: “Murals can do some amazing work in the world, because they live in the places where people live and work, because they can be made in relationship to the people who see them, because the people themselves can have input, if it’s done in a profound way. And that’s what I intend to keep doing as long as I’m standing here on earth.”

[ad_2]

Source link